There’s been a lot of talk about how the government wants to operate more like a startup. Agencies want to model the best of what makes lean startups so attractive: a human-centered mindset that stresses the customer, a streamlined hiring process, failing fast and quick wins. Considering citizens’ rising expectations for sleek digital platforms and easier ways to communicate with government, there’s a lot agencies can learn from their private-sector counterparts about meeting those demands.

But despite the seemingly inherent positive side of a startup culture within government technology, the issues of profitability and a lack of transparency are plaguing the government’s most recent attempt at such a tactic. In March 2014, the General Services Administration commissioned 18F. The digital consultancy group is comprised of technologists, designers, and researchers, who partner with government agencies to develop, test and deploy digital tools and services. There are success stories from customers at the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Federal Election Commission, Department of Education and more.

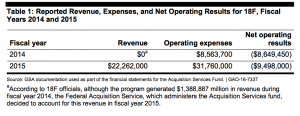

In spite of these examples, well-functioning projects aren’t the only measure of success. Monetary gain, or lack thereof, is also important. However, 18F’s profitability has also been a  topic of concern. In fact, according to a recent GAO report, 18F’s expenditures are still exceeding its revenue.

topic of concern. In fact, according to a recent GAO report, 18F’s expenditures are still exceeding its revenue.

More precisely, as David Shive, Chief Information Officer at GSA predicts, “we’re actually tracking to the date that we expect to be cost recoverable in 2019.” At a September Meritalk event, Shive pointed out that transforming the way the government builds, buys and procures technology is important but also hard to effectively measure.

In the private sector, spending money to make money is just one of the many features of startups that make them unique. It takes time to see monetary returns on investments, but as Shive noted there are several ways to measure returns, including cost avoidance and speed of delivering a product or service. It’s important to remember that there is more than one form of capital. On top of that, 18F is proving the viability of hiring authorities to quickly and efficiently bring people from the private sector on board for short-term fellowships.

According to GSA Administrator Denise Turner Roth, one of the main reasons for starting 18F is to help agencies become smarter buyers of IT and to navigate that process by providing agile acquisition vehicles. Ultimately, smarter buyers are better stewards of the government’s multi-billion IT portfolio.

“I don’t think that anybody can safely say that the 80 plus billion dollars in spending for IT in the federal space is supremely well spent,” Shive said. In fact, a Government Accountability Office report found that “the federal government spent about 75 percent of the total amount budgeted for information technology for fiscal year 2015 on operations and maintenance investments.”

Many of these maintenance investments are really older systems that are outdated and inefficient, but agencies continue to pour money into them — a practice 18F is working hard to change. Most recently, 18F is said to have over 200 employees under its wings. That means more than 200 people across the U.S. who are ready to take on government’s struggle with digital transformation and technology.

But every startup has its kinks, and there are issues 18F must work through. Speaking at a recent hearing, David Powner, Director of IT Management Issues at GAO said that not all of 18F’s goals are outcome-oriented and it has not yet fully measured program performance. “For example, the goal of growing 18F to 215 staff while sustaining a healthy culture and its associated measure of hiring 47 staff do not focus on results of products or services,” Powner noted in his written testimony. “Further, not all of [18F’s] performance measures have targets. For example, seven of the performance measures state that 18F will establish performance indicators, but 18F has yet to do so.”

In addition to the inability to accurately calculate 18F’s outcomes and performance, Rep. Gerry Connolly stressed the importance of GSA and 18F becoming more transparent in their work. “Unless you’ve got a compelling rationale, and a way to mesh this with private sector capabilities, and making note of where is that line between… an 18F assignment [and] one [that] needs to be contracted out,” GSA and 18F are going to continue to receive skepticism.

There are valid concerns about the profitability and the type of work that 18F takes on. But at the heart of all this concern seems to be a fear of being different. All government agencies have known is that hiring takes forever, digital transformation is hard and can be expensive. So when a young, fresh, government organization comes in and commits to solving IT problems in a new way — it’s no surprise that people have reservations.

But the truth remains that at its core, 18F is good and it’s doing good. Providing agencies with better, more efficient IT solutions is what the government needs. 18F proves that the government can function with a startup mentality. In fact, that type of culture may be necessary to continuously improve government operations — despite the inevitable growing pains that all startups face.

“I’m looking at the big picture, and my goal is to see the federal government with 21st century, cutting-edge technology that is cyber protected,” said Connolly, “that is serving the American people, that gives us efficiencies that were undreamt of before and hopefully savings that we can reinvest in ourselves.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.