Strategic planning is touted as essential to a high performing organization. In the government, strategic planning is mandated by the Government Performance Results Acts and by the Office of Management and Budget. But how do you know if strategic planning is really helping your organization? Is strategic planning just another requirement that needs to be fulfilled or does it truly help your organization achieve its mission? How do you assess the true effectiveness of strategic planning in your organization?

Strategic planning is touted as essential to a high performing organization. In the government, strategic planning is mandated by the Government Performance Results Acts and by the Office of Management and Budget. But how do you know if strategic planning is really helping your organization? Is strategic planning just another requirement that needs to be fulfilled or does it truly help your organization achieve its mission? How do you assess the true effectiveness of strategic planning in your organization?

The first step in addressing this question is to recognize that strategic planning is not just a document but is a component of an organization’s strategy process. To paraphrase business strategist Michael Porter, the essence of strategy is to choose which activities the organization will execute. The strategic plan is just the written documentation of those decisions. A strategic plan is only meaningful to the extent that it actually drives decision making throughout the organization.

The question becomes how do leaders decide what is done? Every day, leaders in an organization decide which activities to pursue. They make decisions either based on an effective strategy, or by reacting to unexpected events as they occur and/or drifting through decision points seemingly rudderless and without a considered course.

But both reaction and drift are ineffective ways to focus organizational effort. Reacting to events as they occur wastes resources and dissipates organizational effort on activities that do not contribute to mission success. Drift relies on experience to set a course of action leading to an inability to adapt to uncertainty and the unexpected. Using an effective strategy to make decisions focuses effort on taking advantages of opportunities and overcoming critical challenges. High-performing organizations cannot tolerate the lost opportunities and waste that are inevitable without an effective strategy.

So we reframe the question to be, “How do you assess your organization’s strategy process?” An effective strategy focuses resources and effort on activities that directly contribute to achieving the organization’s mission. The starting point of an effective strategy is a clear understanding of the desired outcomes. Without a clear destination, there is no real criterion by which to judge which actions ought to be taken. Now, many organizations do not have clear goals, but usually that just means the leadership has made the default decision to continue doing whatever was done in the past. In today’s dynamic and competitive environment, drifting with the currents inevitably leads to crashing upon the rocks. To thrive leaders must pick a destination and actively steer their organization towards it.

Too often leaders view the articulation of clear outcomes as the end of the strategy process. Often you see the captains of industry and government selecting bold strategic goals as the destination for their organizations and then promptly (and somewhat mysteriously) “returning to their quarters,” ignoring the critical need to chart a course. These leaders sometimes present their bold goals with great fanfare and publicity, yet leave it up to their crew to figure just how to plot the course and navigate to the newly articulated destination.

It’s closer to operational truth that once a goal or destination is selected, a ship’s leadership must carefully consider their current location, the currents, submerged obstacles, the availability of food and fuel, the state of their crew, the condition of the ship and their general orders. In short, leaders need to confirm that it is possible to get to the desired destination and, if it is, identify the best course of action to make the journey and then share this with the rest of the crew.

The key to charting an effective sequence of strategic actions is to develop a realistic theory of cause and effect. A strategy’s basic task is to identify specific actions that are expected to cause specific results. The heart of any strategy is a theory about why the specified actions will lead to the desired results. A good strategy clearly articulates the “why.” It explains how the actions taken will cause desired results. Like any good scientific theory, a strategy theory must be empirically verifiable. A strategic theory must be based on a proposition that can be tested in the real world.

The power of a cause and effect theory is based on a true understanding of the environment within which the organization must act. Techniques such as environmental scans can help identify the salient features of the environment that determine whether the cause and effect theory will play out as expected. The challenge that organizations face is that the environment is not static. Often organizations simply assume that the future will be the same as the present. Such organizations tend to implicitly adopt a strategy of drift. Yet, as we all know, the environment that we all operate in is inherently dynamic. Understanding the dynamics of change, being able to anticipate the direction that it will take, is the key to a successful strategy.

Former Intel CEO Andy Grove’s concept of a ”strategic inflection point” teaches us that successful organizations tend to build their structure and processes to reflect a specific view of the future (see Andrew Grove, Only the Paranoid Survive, 1996). They design their structures, develop capabilities, promote leaders and generate a set of values and a culture based on an understanding that has generated success in the past. Reliance on familiar practices and patterns of thought enables the organization to continue to succeed, as long as things do not change in any fundamental way.

Yet, as Grove points out, they always do. The first signs of change are imperceptible and too often easily dismissed. Yet at some point, the inflection point, the change overwhelms the old way of doing things and the organization, trapped into the old way of thinking and acting, fails to adapt and begins to fail.

To avoid missing a strategic inflection point, organizations must do two things. First, they must learn to identify the sources of disruptive change. Second, they must develop a set of actions that will enable the organization to accomplish its mission under changed conditions. The challenge is that an organization faces multiple possible futures. The complex array of variables that any organization deals with may combine into many different combinations. Changes in market conditions, government policy, supply chain, technology, and the labor force can all have a drastic impact on an organization’s ability to achieve its mission. This complexity both creates signal noise that makes it difficult to identify the changes that will have the largest impact on the organization’s future and makes it more difficult to identify which actions will best enable the organization to thrive.

The set of strategic actions must be coherent. They must be focused toward achieving strategic objectives. They must be aligned and operationalized. There needs to be thought out and coordinated sequence of actions that will cause the desired effects. We label a coherent set of actions as the “execution concept.” The execution concept is more than just a list of actions. Too often strategic plans are a laundry list of actions that are poorly coordinated and whose effects may even cancel each other out. An effective execution concept mitigates this risk by explaining how planned actions fit together both in terms of sequence and how they work with each other. The execution concept may be articulated as the portfolio of activities and initiatives that the organization will execute. Tools such as Kaplan and Norton’s Strategy Maps may be used to show the logical relationship between activities and initiatives.

Organizations developing a long-term strategy face tough decisions about which capabilities to develop. As they develop an execution concept, leaders need to understand whether their organization has the capabilities required to accomplish the identified tasks. If they do not have the required capabilities, then they need to determine how they will be acquired. Decisions about what capabilities are necessary and how they will be acquired is a part of strategy that is often overlooked. Yet, in many ways decisions about capabilities are the most important output of the strategy process.

The final key to an effective strategy is governance. Strategy is more than a plan. Strategy is an ongoing process of evaluating the environment, reviewing results, making adjustments and sometimes scrapping the plan and reinventing a new strategy. This process is often tied to a set schedule. In the federal government, the strategy process is governed by the Government Performance Results Act which requires a new strategic plan every four years. This approach can be dangerous. The world does not follow set pattern. Uncertainty and chaos can impose radical new challenges and open up incredible opportunities at any time. A bureaucratic process can impose rigidity that stifles effective strategy. The danger is that strategy becomes a bureaucratic routine of collecting forms, creating PowerPoint slides, decision briefs, and writing long plans that end up in an ignored binder as people go about their business. Strategy governance must support agility and innovation, not stifle it.

An effective governance recognizes the fluidity and uncertainty are unavoidable. Such a process exploits opportunity and manages risks as they occur. It is adaptive. The Toyota approach to strategy is to develop a set of problem-solving skills and processes that are deployed whenever a trigger event occurs. When problems or opportunities are identified, it triggers a sequence of analysis, decision making, and action. The flexible Demming approach of Plan, Do, Check, Adjust provides a useful framework for a flexible strategy. This is difficult to implement for tactical issues but even more hard for strategic issues. It turns strategy from a bureaucratic process of filling out forms into a disciplined method of organizational learning.

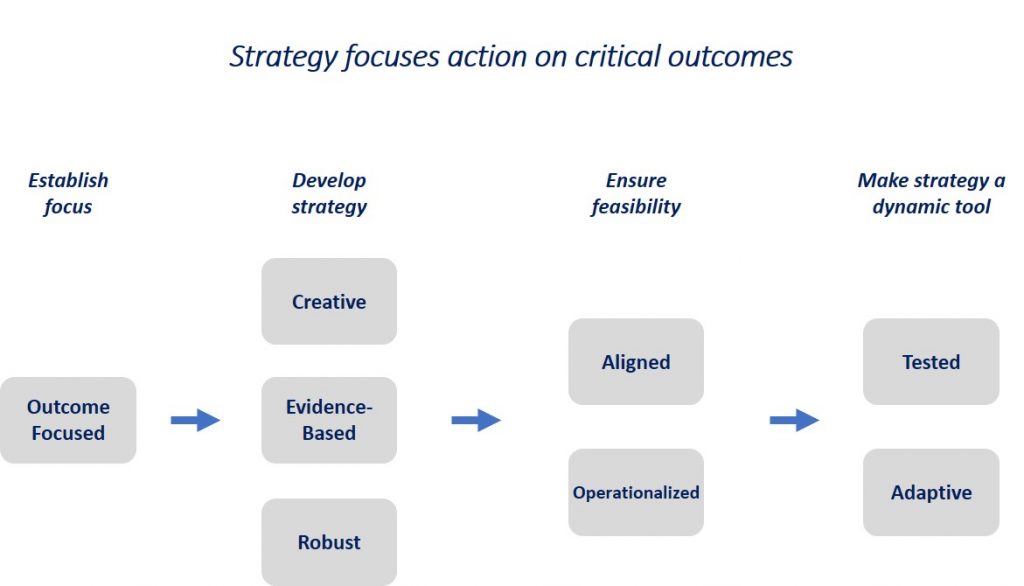

Strategy can take many different forms. From detailed, formal strategic plans from organizations with large staffs dedicated to that purpose, to a rapid strategy made by a small group of senior leaders. The particular form is not important. What is important is whether strategy performs its role in focusing the efforts of the organization. No matter what the size or shape, when assessing a strategy’s effectiveness, concentrate on the following attributes.

The Pathfinder Performance Model™ identifies seven key attributes of an effective strategy. These are the markers we use to evaluate the effectiveness of strategy within an organization. To assess the effectiveness of vision within your organization, use the following checklist

- Is our strategy outcome focused? Does our strategy focus the organization on achieving mission-critical outcomes?

- Is our strategy creative? Does our strategy break through self-imposed limitations on what is possible to generate innovative options?

- Is our strategy evidence-based? Is our strategy process built on an accurate understanding of the internal and external operating environments?

- Is our strategy robust? Is our strategy based on a clear logic of how cause and effect work within a complex and dynamic system, now and in the future?

- Is our strategy aligned? Is our strategy aligned with and fully supportive of the vision and the actions of the organization, and vice versa?

- Is our strategy operationalized? Can our strategy can be executed with capabilities that we have or can acquire?

- Is our strategy tested? Are our strategies subject to rigorous performance measurement and evaluations to ensure that only the most effective actions are continued?

- Is our strategy adaptive? Does our strategy pro-actively adjust to new facts and new opportunities?

If you can answer yes to these questions, then you can have reasonable assurance that your strategy is an effective force driving your organization to higher performance. If you answered no to one or more of these questions, then you have an idea about where to focus your improvement efforts.

Dr. Andrew Pavord is a GovLoop Featured Contributor. He is a former government executive who currently is the CEO of the Federal Consulting Alliance. He led budget processes for DC government, SBA, and Treasury, managed department headquarters operations for Treasury, and served as chief of staff to the CFO of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Read his posts here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.