|

| Street Fighting Years |

Preamble

You may have noticed that I didn’t publish last week; as a result this week’s article is both weightier and lengthier. Accordingly I decided to experiment a bit by providing a TL;DR version of the article up front, namely: Public Engagement via Social Media + Big Data Analytics = Future of Public Policy.

How I got there …

To say that either Linked Data or Big Data are new would be a mischaracterization; to say that they are still new to government on the other hand is likely a fair assessment.

Linked Data: A Primer

For the unfamiliar, linked data is simply a way of structuring data so that it can be easily aligned with other data sets; linking data together increases its usefulness by providing richer strategic overviews or by facilitating a greater depth of analysis. Tim Berners-Lee first wrote about it in 2006 and delivered a TED talk on it in 2009 and if you are interested in seeing the quality of public policy analysis that properly linked data can inform Hans Rosling’s demonstration is a prime example.

Big Data: A Primer

Big Data on the other hand is a collection of data sets so large and complex that it becomes difficult to process using traditional data processing applications. Large consulting firms such as McKinsey, Deloitte and IBM have already published a lot of material on Big Data and while the majority of that material focuses on how its application to the private sector there are surely lessons in it for public sector policy makers.

Abundance is the common denominator

Whether you are talking about linked data or big data – or more simply calling it the data deluge – the fact of the matter is that the information landscape has shifted from scarce to superabundant. This shift is likely to have profound implications for the public sector; many of which are still ahead of us and will undoubtedly involve profound growing pains.

How could data abundance impact how governments do policy?

As a starting point, bureaucrats can anticipate a renaissance of the language of data driven decision making within the larger nomenclature of evidence based policy making. Make no mistake, these terms are still very much in vogue in bureaucratic culture but likely require a fresh definition given that the nature of what underlies them – namely the availability of detailed data, and as a consequence analysis – will improve significantly over the foreseeable future. As a conceptual framework, it would look something like this (click to enlarge):

Note that the framework recognizes that data driven decision making must be understood within a larger context. In this type of environment, policy makers will need to consider the types of data being collected, the analysis being performed and decisions being made across all levels of government: municipal, provincial, and federal. Under this type of model, there is a significant probability that analysis will expose untenable points of incongruence between the highly contextual and specific insights pulled from the intersecting data points and governments’ tendency to pursue universal, one-size-fits-all, policy solutions. In other words, providing policy makers with a deeper understanding of the complexity of a particular public policy challenge is likely to yield equally complex public policy solutions.

The complexity of the long tail

Bureaucrats can also expect to continue to see their monopoly on information erode; to realize that many of the levers of change are outside the reach of traditional approaches; and take stock of the fact that there a very different skill set may be required to accomplish their mission.

In other words, under these conditions they may have to formally recognize what David Eaves calls the long tail of public policy. In The Long Tail of Public Policy (Open Government: Collaboration, Transparency, and Participation in Practice) Eaves argues that there is a tremendous amount of capacity for public policy in the long tail and that the widespread availability of free communications technologies is starting to unlock that potential (click to enlarge):

Eaves goes on to discuss the rise of “patch culture” online indicating that it is spilling over into both public policy and service delivery, arguing that citizens are able to create “patches” that improve government service delivery when they are given access to basic raw data, how decisions get made and the underlying system of how government works. Eaves points to an innovative service like FixMyStreet as a prime example of how the long tail of public policy can be activated under the right conditions. What is interesting about this particular example is that not only is its origins in the long tail but so is its final resting point. In other words, FixMyStreet is a niche solution to a niche problem.

Closer to home, the Ottawa based company Beyond 2.0 recently launched a real time bus arrival screen levering the city’s data before the municipality could get its ducks in a row and do it themselves. The company applied a “patch” solution to an acute problem faster, better and cheaper than it could have been done otherwise.

What the patchwork can teach policy makers

As this patchwork becomes increasingly elaborate we can expect policy makers inside the walls of government to take notice, to expand their realm of the possible, and to adopt more the approaches used outside their walls. In this vein, policy makers may want to purposely turn their attention to fields like design and manufacturing to borrow lessons from fields such as rapid prototyping. Rapid prototyping is an approach that places considerable importance on:

- Increasing effective communication;

- Increasing viability by adding and eliminating features early in the design

- Decreasing development time;

- Decreasing costly mistakes; and

- Decreasing lifetime before obsolescence.

At first glance, these objectives may not strike you as anything new. After all, bureaucrats have been “finding efficiencies” along this particular supply chain for some time now; that said supply chain management and rapid prototyping are two very different things. The former is akin to sustaining innovation (innovation that helps you better serve your current market) while the latter is akin to disruptive innovation (innovation that allows you to serve a new or emerging market) (See: Innovators Dilemma by Clay Christensen).

This is not surprising given that large organizations have endured because they focus on delivering their core business while faltering at their margins where (more disruptive) innovation happens (see: Finding Innovation). However, if governments want to be able to serve emerging markets – which is to say meet evolving citizen expectations – then they will likely need to scale back sustaining innovation efforts and invest more readily in disruptive innovation. This seems like relatively new ground to break given that bureaucracies are often too busy to innovate. It is highly probable that the emergence of Big Data will help make this shift possible. However, pivoting in this direction will not be easy for large monolithic organizations that require not only a change in the cultural mindset but also a changes in the available skill sets of those called upon to do the actual work.

New Skills for Communicators

There are likely three very specific roles for modern communicators. Communicators need to be able to provide strategic guidance on matters of public policy and the culture writ large, and steward technological and policy modernization while engaging the public using new communications technology (e.g. social media) (See: The Long Tail of Internal Communications). In order to carry out these duties effectively, communicators will need to be able to:

- Find, verify and link stakeholders and their viewpoints;

- Weigh a multitude of inputs from multiple sources;

- Draw out highly contextual and relevant insights; and

- Transform those insights into practical communications advice.

New Skills for Analysts

When it comes to analysts the shift sounds simple but is actually quite profound. Analysts will need to move away from report writing and the standard 6-month production cycle towards in depth data analysis, insight formulation and feeding real time dashboards used by (data driven) decision makers. Since the numbers can’t actually speak for themselves, it will be important that analysts are able to:

- Find, verify and link (or liberate) useful data sets;

- Analyse complex data pairings (again, different than report writing);

- Draw out highly contextual and relevant insights; and

- Transform those insights into policy options.

The future of policy development hinges on two things

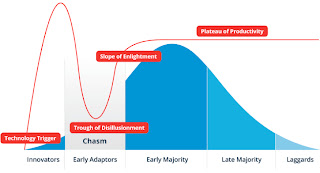

The future of policy development hangs on two things: (1) enhanced public engagement through social media and (2) data driven decision making and while bureaucracies aren’t quite there yet, evidence suggests that it at least now visible on the horizon. For example, the recent institutional response at the senior levels of government – the formation of the Deputy Minister’s Committee on Social Media and Policy Development – signals the arrival of the early majority to Social Media indicates that Social Media as policy input has in fact crossed the chasm (click to enlarge):

There is also growing evidence that suggests that Big Data is about to cross the chasm in the private sector, meaning that it is still within the realm of early adopters in the public sector.

Success belongs to those who can balance them

In a communications heavy and data rich world, unlocking the long tail of public policy and exploring the richness of niche solutions to highly complex policy challenges will likely continue to be one of the most significant developments in the policy environment in the next 10 years.

The key to achieving this is balancing both sides of the house: public engagement through social media and in depth and contextual Big Data analysis; meaning of course that Public servants who have the skill set to do both are bound to be in demand.

Originally published by Nick Charney at cpsrenewal.ca

subscribe/connect

Great overview! My one quibble is that enthusiastic views of government and big data like this tend to underestimate the impact on cost and analysis potential of messy, nonstandardized, or incompatible data. One of concern is that, because of some of the difficulties associated with such messy data, officials might tend to favor use of available but incomplete data rather than devote necessary resources to ensuring accuracy and completeness. Things always look better at 30,000 feet than they do at ground level and, as the article points out, having the right analytical skills available to government decisionmakers is definitely a move in the right direction.