As digital services teams increasingly focus on the accessibility of their work, they often find themselves in unfamiliar territory. Whereas the accessibility of web content has been guided by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) since the 1990s, document accessibility is a more recent focus.

My own knowledge of document accessibility — specifically, PDFs — came through a project that involved designing a complex web form intended for state officials. In the midst of the project, our team was thrown off-guard when we learned that the PDFs generated by the web form did not comply with Section 508 federal government accessibility standards.

As a result, our team learned how to audit and fix PDF accessibility issues on the fly. One teammate spent countless hours on Adobe Acrobat checking hundreds of pages for accessibility flags.

My company, Coforma, has long prioritized accessibility, but our initial focus was on web accessibility. We learned a lesson from this experience with PDFs. After relying on third-party services to help us meet 508 compliance for documents, we hired our first in-house document accessibility specialist, Evan Burnett. According to Burnett, what we experienced happens regularly on projects.

“[Misunderstandings around PDF accessibility] leads to bottlenecks and projects going over deadlines. Throughout my career, this has been a persistent issue.” He shared with me some things he wished everyone building government technology understood better about PDF accessibility:

Misconception #1: PDFs Don’t Need to be Accessible

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about one in four adults in the United States has some type of disability. Making websites accessible to users with disabilities is increasingly a priority at all levels of government: from local and state to federal. However, the revised Section 508 standards expanded accessibility requirements to include electronic content like documents, presentations, social media content, blogs and emails in addition to web pages.

Accessibility for documents is not as well known or understood as it is for websites. In fact, prior to my web form project, I assumed that PDFs were inherently inaccessible as a file format and that they required digitization to become accessible. I wondered if it was even possible for a screen reader to read a PDF. I learned later that a PDF is actually the most commonly used file format for sharing documents and that many individuals rely on PDFs to accomplish day to day tasks.

Misconception #2: Automated Tools Catch and Fix All Accessibility Issues

Burnett explained that the machine learning technology of automated tools is not advanced enough to catch and fix all accessibility issues. Even with a thorough audit using an automated tool, the final document requires a manual check in order to ensure accuracy and usability. Burnett shared some examples of accessibility issues overlooked by automated tools in his article Accessibility vs Usability in PDFs: What the Accessibility Checker Doesn’t Catch.

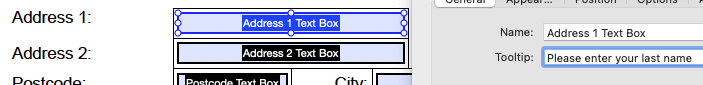

Automated tools overlook issues like inaccurate or insufficient alt text for images and links, along with broken links. For instance, an automated checker only determines whether alt text or form field labeling exists, not whether the description is correct. See an example below of where the form field label (i.e. Tooltip) conflicts with its corresponding field:

Even so, automated tools are a great starting point and useful for minimizing manual work by quickly surfacing simple accessibility issues. Burnett recommends the following tools for a preliminary audit of accessibility issues. Please note that many work best with a Windows operating system:

- Acrobat Pro Accessibility Checker

- PDF Accessibility Checker (PAC) 2021

- Colour Contrast Analyser

- NVDA – screen reader for spot checking

- CommonLook PDF

Conclusion

According to Burnett, the manual process of auditing and fixing document accessibility (or “remediation” as it’s known by insiders), can be labor-intensive and often takes longer than anticipated. It also requires a certain level of expertise that most people don’t have.

Burnett suggests that teams run the entire document through an accessibility checker early on in order to allocate the right amount of time to the remediation process. In general, longer documents that are dense with data tend to lengthen the process (data-density can be measured by the number of complex tables, form fields and complicated graphics).

The University of Colorado details a quick accessibility check on determining how much remediation might be needed later on: (1) whether the text is actually text as opposed to an image, (2) whether any content is tagged. If the answer is no to both, the PDF is definitely inaccessible and requires remediation.

What are your experiences with accessible documents? Coforma will be releasing a remediation checklist and a how-to guide on manual accessibility checks in 2023. Please stay tuned!

Julie Kim (she/her) is a Senior Product Designer at Coforma with nearly a decade of experience creating simple, effective, and engaging websites and mobile applications. Prior to her role at Coforma, she was a user experience lead at the city of San Jose. In both roles, she’s helped guide efforts toward building more inclusive, human-centered government services.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.