Most of us work in government because we know the impact government can have on our communities and stakeholders. We feel called to service for our communities, and we care about them. But we’re constantly unsure of how our services are impacting our stakeholders.

For-profit companies can tell how they’re doing by their sales; governments need to ask their communities how they’re meeting their needs.

So we ask for feedback all the time. But sometimes it hurts. It can personally hurt to be told that the project you’re leading or the service you’re providing isn’t working for the people you’re there to serve.

Put your mask on first, then help others

Food service and retail workers will tell you that every interaction with a customer is a performance. Serving staff put on something called a retail face, and it’s a survival skill. Retail face is the employee’s protection against the unsolicited feedback that retail staff get from customers. Retail face helps separate the individual from the system outside our control.

But you won’t be able to change the world if you get burned out and leave your job in government. So we’ve got to find a way to keep ourselves from taking the feedback personally. Even more, we need to ask for feedback in a way that helps us drive better and more sustainable results for our communities.

Breaking the “Us/Them” & “Positive/Negative” frameworks

Stakeholders can often see themselves as righteous, the representatives of reason and wisdom. Against them stand the systems of oppression and the people who represent it (that’s us).

This may seem oversimplified, but it’s natural. Understanding conflict as simple binary choices is as old as humanity. Older, even, snap judgments have their roots in fight-or-flight instincts located deep in the ancient parts of the brain.

Our challenge is to break out of this instinctual conflict and engage in a more productive exchange of ideas.

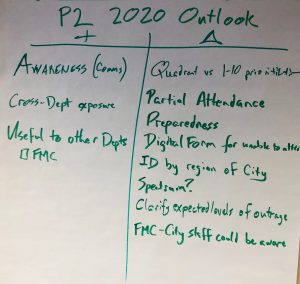

One of the more useful tools for capturing feedback is the Plus/Delta chart. Plus/Delta takes the familiar “positive vs negative” feedback framework, and turns it into a more “all of us vs. the problem” mindset. The Plus/Delta chart allows participants to give feedback but puts them into the role of problem solvers. What worked well? What would you change? These questions enable a group to unpack a situation and explore improvements together.

Plus-Delta feedback tool in use

If you’ve used Plus/Delta charts to debrief or gather feedback, you know that it overcomes the dead-end of “what did you like/what did you hate” by leading into a more productive conversation. Much like IDEO’s “how might we…” question, the Plus/Delta framework opens the conversation for innovation and collaborative problem-solving.

It’s a simple shift, changing “what did you like, and what did you hate?” to “what should we do more of, and what should we change?” It’s a simple reinforcement of the concept that we’re all working to make something better. And that, to me, is the essence of government.

It’s easy to focus on the negative comments you receive. We’re actually wired to focus more on the negative feedback we receive than on compliments. So let’s stop framing feedback as a negative. Even the most die-hard sports fans critique their team’s play. It’s not because we don’t support them. We want our sports teams to perform well, so we yell at the television.

The Plus/Delta exercise places the community and their government staff on the same side of the table, working together to solve the problem. In the same way, government leaders must understand that the goal is not to get it right the first time and only receive glowing praise.

“Politicians aren’t allowed to make mistakes”

Authority in most government organizations eventually rolls up to someone who was put in place by an election. Elected officials tend to their reputation carefully, so it can be hard to embrace feedback.

But never accepting feedback means that you’re never going to learn anything you don’t already know. When we re-frame the feedback, when we expect to learn over the course of a project or issue, we demonstrate both a willingness to grow and the humility to listen to the opinions of others.

The idea of a “learning organization” is decades old. In 2020, elected officials and public organizations who expect that their involvement in their community took place at their election are either out of office or should expect to be soon.

What feedback do you have? How might we improve community participation in debriefing sessions, and how can we develop?

Also, if you want to plus/delta this blog post, I’m all ears…

Jay Anderson is responsible for digital engagement and public processes at the city of Colorado Springs. Jay holds an MPA from the School of Public Affairs at the University of Colorado – Colorado Springs, where he also serves as the Chair of the Dean’s Community Advisory Board. Jay focuses on the point of engagement between the community and its institutions, creating programs that give a voice to people who want to have an impact on their government.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.