One evening in 2016, I ran across an fascinating Facebook post. It read: “The Silence Breakers were named Time Magazines Person of the Year. I want to give credit to my mother, the real silence breaker, Diane Williams. She was a trailblazer in the fight against sexual harassment in the workplace.”

A 1976 Jet Magazine article accompanied the salute. It pictured a radiant woman under the headline: “Sex Harassment Ruled In Firing of D.C. Woman.”

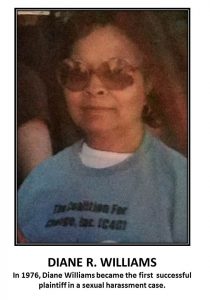

To my surprise, the woman in the picture was my late friend –Diane R. Williams. Before her passing in 2016, Diane had worked as an Equal Employment Opportunity attorney with the Government Accountability Office. She had also volunteered as the Legislative Chair of the Coalition For Change, Inc. (C4C), an advocacy organization I founded to address racism and reprisal in the federal sector.

Over the years I had known Diane, she never shared with me the scars she sustained after suffering injustice while a member of the United States labor force.

Filled with amazement, my eyes scanned the posted Jet article. Line by line, I read of Diane’s courageous fight against the U. S. federal government as I mused of how the graduate of Howard University with the Juris Doctorate from George Washington University Law School who had a rich reason to boast, never did!

Prompted to learn more, I began searching the Internet. I soon discovered the year I studied in grade school, Diane worked as a Communication Specialist for the Department of Justice. She entered the work force in January 1972. However, she served only eight months. By September 1972, the Justice Department fired her after she refused to sleep with her supervisor. Ironically, her supervisor’s first name sounded the same as the Hollywood film producer, “Harvey” Weinstein. Like Weinstein, Diane’s boss, “Harvey” Brinson,” loomed at the center of a sexual harassment claim. Much like Weinstein, Brinson wielded a powerful presence. However, this “Harvey,” reigned as the Director of Community Relations within the Nation’s premier law enforcement agency.

Still, rather than shrink away quietly, Diane, at 23 years-old, broke from the silence of the ’70s. She confronted her formidable harasser. She ignored the workplace notion – “boys will be boys.” She spoke up before the #MeToo movement, at a time when sexual harassment was seemingly a normal condition of employment for women in the workplace. As required of federal employees, Diane first filed her claim in-house with the employer who fired her. Predictably, the Justice Department – the named defendant – failed to find that it had discriminated. Therefore, Diane launched a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. In turn, the government motioned the court to dismiss her case. During court proceedings, the Justice Department stated plaintiff Diane R. Williams did not have a legal standing under the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Act) to bring a “sexual harassment claim” into court. (The Act bars employers from discriminating against workers on such basis as race, color, or sex.)

Despite the government’s relentless maneuvers to end her lawsuit, armed with legal representation, Diane successfully argued her case. She argued the harassing conduct she complained of fell within the definitional parameters of “sex” discrimination under the law. Resultantly, she won her case known as Williams v Saxbe [Civil Action No. 74-186]. In winning, Diane became the first person in America to take a sexual harassment into a U.S. District Court and to obtain a ruling that sexual harassment forms sex discrimination under the Civil Rights Act.

Before Diane took her case into court and won in 1976, judges held a narrow view of “sex” within the bounds of the law. They had ruled that the law only protected a woman from sexual discrimination in mostly outward forms, like when a supervisor denies a woman a promotion because of her “gender.”

But, following Diane’s landmark victory in Williams v Saxbe (D.D.C. 1976); other courts began recognizing that “quid pro quo” sexual harassment forms sex discrimination under the Act. Notably, prominent cases like Barnes v Castle (D.C Circuit, 1977), Bundy v. Jackson (D.C Circuit, 1981), and the Supreme Court case Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson (477 U.S. 57, 1986) all found that workplace quid pro quo sexual harassment violated the Civil Rights Act of 1964. [Quid Pro Quo “something for something” harassment occurs when an employer requires an employee to submit to unwelcome sexual conduct as a condition of employment.]

Now, some 42 years later, Diane R. Williams’ pioneering opposition to sexual harassment in the workplace helps victims of sexual harassment. She paved a legal path for women who choose to file such harassment suits against their bosses.

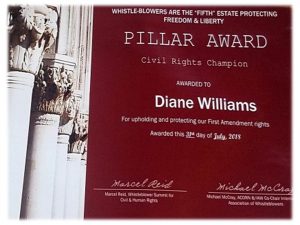

To recognize her historic achievement, the whistleblower community honored Diane R. Williams posthumously with a Pillar Award during the 2018 Whistleblower Summit for Civil and Human Rights. Event organizers presented the “Civil Rights Champion” award to Diane’s beloved son, Kyle White, who in a Facebook post shined the light on his mother’s monumental victory benefitting the #MeToo movement.