I’m a geographer, so I tend to think of most problems as geography problems. This approach has typically helped me. It certainly got me through grade school history. If I could see a map, I got it. Today, when I read the news, if I don’t know where the subject of the news story happens, I look it up. This generally makes for a lot of map searches. My wife is actually happy that I bring my smart phone to the breakfast table, as its replaces the rather large Rand McNally atlas that I once kept nearby.

I was listening to a podcast recently. It was a collection of thoughts deliberating the latest updates of the many legal battles over redistricting. The interviewer used a phrase that caught my attention. While describing the winners and losers in redistricting, he said, “Geography is destiny.” It is a phrase that owes its origin to early theories of geopolitics. Isn’t that fitting? It’s originally credited to Napoleon, prior to his army invading Russia. Hmmm, we all remember how that turned out.

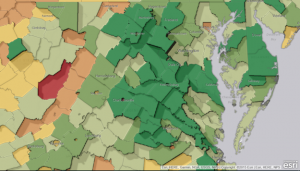

All the same, I think the phrase – as it was applied to redistricting – is a good one. In fact, with my geography-centric way of thinking, everything about redistricting is a geographic problem; perhaps, a geo-political problem.

The Census is an Enabler

The US Census exists, originally, to facilitate the reapportionment of congressional seats, assigned to each state, based on the population. Once the number of congressional seats are assigned, the states are responsible to divide up the state into districts – redistricts – dividing the population into these districts so they can elect their representative. As the nation entered the mid-20th century, better small-scale geographic data was required to facilitate the Census results, and the Voter Rights Act.

The first Census geographic base files, referred to as GBF-DIME files, were created. In short, the DIME files helped digitize the geographic boundary data that would be used to redistrict. The DIME was built in the 1970’s and improved for the 1980’s redistricting. It eventually evolved to become what we know today as the TIGER files. This, along with the commercial use of DIME and then TIGER – with its small area data – contributed to the development of what we now call Geodemographics.

In short, geodemography is the study of people based on where they live. Geodemographic systems estimate the most probable characteristics of people based on the pooled profile of all people living in a small area near a particular location. The key phrases here are: estimate; probable characteristics; and near a particular location.

Let me translate: humans are habitual and herd together in a somewhat predictable manor. If you don’t believe me, checkout this Zip Code Lookup tool. It’s how the drug stores know which products to stock; it’s how restaurants pick new locations; and it’s why you get that blue envelope in the mail every Tuesday with the ads for the dry cleaner, the pizza place and the gutter repair guy.

Self-Sorting or Just Freedom of Choice

So, in a sense, we Gerrymander ourselves. Of course, this excludes historic and unscrupulous redlining practices. As an example, people with college degrees, especially those with advanced degrees, tend to settle in urban-like neighborhoods. People with traditional backgrounds, tend to gravitate to the exurbs and rural areas. The intriguing part is this: liberals who move into conservative areas become more conservative over time; and conservatives who move into liberal areas become more liberal over time. While we don’t necessary vote with our feet, we do pick where we live, and we live in neighborhoods that reflect who we are.

Communities of Interest

Each of us has a cognitive map of our community; a place we call home. We assume that everyone in our community agrees with us. Defining just the word “community” is hard enough and it has the help from defined geographic boundaries – “I live in the town of…”; “my neighborhood is…”; “my zipcode is…”

Defining a community of interest takes on a whole new complexity because it includes non-geographic features. The Alabama Constitution defines it as “an area with recognized similarities of interests, including but not limited to racial, ethnic, geographic, governmental, regional, social, cultural, partisan,or historic interests; county, municipal or voting precinct boundaries; and commonality of communications.”

Excuse the over-simplification, but my very non-expert take on the case(s) currently under consideration at the Supreme Court – as of last Friday, both Wisconsin and Maryland – are basically saying that political affiliation is a community of interest that needs protection.

There Are No Redistricting Angels

Historically, most voters pay little attention to redistricting. This has contributed to why partisan politicians have been so effective in manipulating for so many years. Of course, both sides try to maximize every advantage and claim it as a directive as their due. The answer, however, is not turning every zero-year election into a gerrymandering arms race.

Like Law and Sausage Making

As I discussed in last week’s blog, there is a growing angst and mistrust about redistricting. Like laws and sausage, we never really see the process of redistricting. Some states have started to use appointed bodies or commissions, but these constitutional re-structuring bodies are still only a means to improving the process of redistricting, and not the end.

Redistricting is a game of tradeoffs. Not everyone is going to end up happy. It’s easy to poke fun at oddly shaped districts, and humans typically vilify anything we dislike. As a result, we’ll always have the specter of Gerrymandering. But, if there was an opportunity to provide citizens with the data and tools used by the legislators, transparency could occur.

With transparency of process, not to mention the valuable lessons in civics, accountability is created. If we can examine and explain the reasons given why districts are shaped that way, we’d have the chance to trust.

Join me next week, for a third installment, where I’ll discuss the ideas of open redistricting and rebuilding trust back into the process.

Richard Leadbeater is part of the GovLoop Featured Blogger program, where we feature blog posts by government voices from all across the country (and world!). To see more Featured Blogger posts, click here.

This is an interesting and important topic to discuss. Thanks for sharing Richard and looking forward to next week’s blog!

Loved this and am so curious to read next’s week post about how to reintroduce trust into this process! It is sorely needed.