![]()

In his now infamous speech at Rice University in 1962, President John F. Kennedy outlined a bold goal; to go to the moon. In this speech he famously enumerated the challenges; “Send a man 240,000 miles away, in a giant rocket three hundred feet tall, made of new metal alloys, some of which had not yet been invented, capable of withstanding heat and stresses several times more than have ever been experienced, fitted together with a precision better than the finest watch, carrying all the equipment needed for propulsion, guidance, control, communication, food, & survival, on an untried mission, to an unknown celestial body, and then return it safely to earth, reentering the atmosphere at speeds of over 25,000 mile per hour, causing heat about half that of the temperature of the sun, and do all this, and do it right, and do it first, before this decade is out.”

Most people remember these incredible elements of Kennedy’s speech, but they may forget how he began. He opened by saying, “We meet in an hour of change and challenge, in a decade of hope and fear, in an age of both knowledge and ignorance.”

These words are just as appropriate today as they were fifty-four years ago. We surely face significant challenges in this era. In particular, our public servants are being asked to do more with less. In the federal government, executive branch employment is about comparable to the size it was at the time Kennedy was in office, despite the fact that the U.S. population has nearly doubled since then, and technical complexities in an increasingly global world have increased exponentially. To cope, we’ve focused chiefly on maximizing our efficiency, establishing procedures to help streamline processes. Yet still we face daunting challenges. Perhaps we should take a page out of the Apollo project’s playbook.

Liftoff of Apollo 11

Increasing Complexity

As our work becomes more complex, we must recognize that efficiency alone, while a noble goal, will not save us. A focus on reductionist processes leads to further specialization, stratification, and segmentation at the cost of holistic knowledge. With such a focus, it is no small wonder that many public and private sector organizations are now lamenting a perceived lack of future leaders. Leadership demands a holistic, conceptual understanding of an agency, not just one small piece of the overall puzzle. When we place people in boxes with blinders on in the name of efficiency, we remove the capability for holistic understanding.

Like NASA of the 1960s, we have a great task ahead of us. Within the public sector we have many individual teams doing great work. However, many exist within their own individual silos with little communication or collaboration. In NASA’s case, this meant progress was slow, and gaps in communication led to interface errors in integration between team efforts. Most of these problems arose from a lack of transparency and information-sharing. Without fluid integration between their efforts, a rocket could not get into space. Indeed many would routinely blow up on the launch pad. In one such instance, something as simply as using the wrong extension cord led to a cascade of electrical sequencing system failures prior to takeoff of an Atlas rocket. In another high-profile recent example, the $125 million dollar Mars was lost because one team used metric measurements, and the other imperial.

The Solution: Systems Management

For NASA, the solution to this problem was Systems Management. Based on the principles of Systems Thinking, Systems Management presumes that one cannot understand their part of a system without having conceptual knowledge of the whole. While specialization is great for efficiency & productivity and can work when problems and solutions are simple (like an assembly line), as efforts become more complex, gains in efficiency are increasingly offset by a lack of holistic knowledge about the bigger picture. NASA’s implementation of Systems Management also had the effect of fostering incredible innovation, empowerment, and creativity among NASA employees, which led directly to the acceptance of novel suggestions saving countless time and money, and which might otherwise have gone undiscovered.

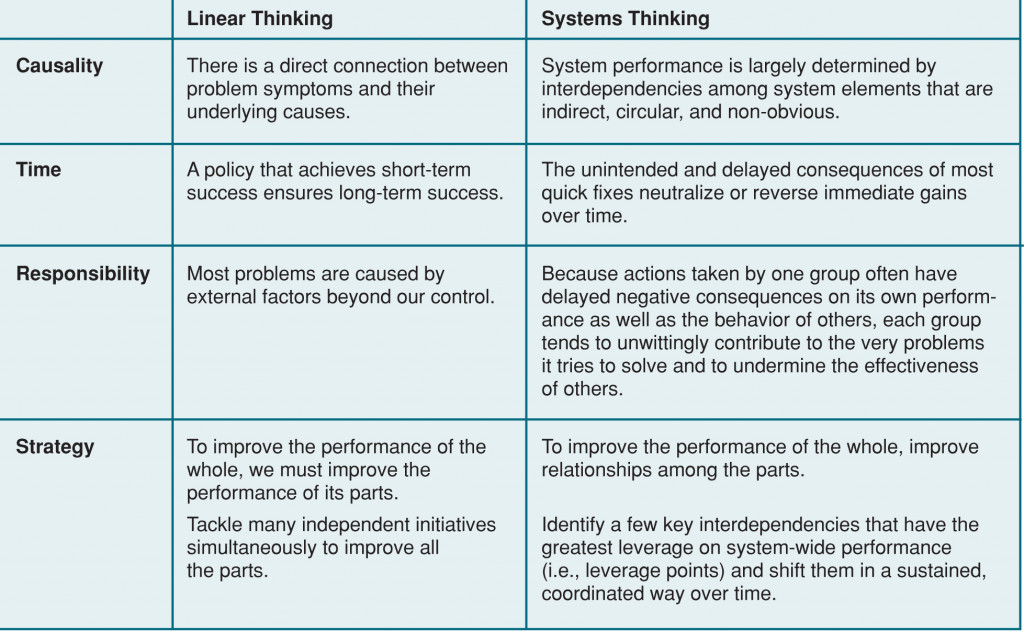

Linear Thinking vs. Systems Thinking

For an example of what can happen in the absence of holistic knowledge, look no further than the European efforts of the Europa project. As with Kennedy’s vision, the Europa lunar mission united many countries of Europe with the goal of reaching the surface of the moon. Like Apollo, they had similar access to expertise and resources and utilized a division of labor within small teams. The United Kingdom provided the rocket’s first stage, France built the second, and Germany the third stage. The rocket carried a satellite designed and built in Italy, telemetry was developed by the Netherlands, while Belgium developed the ground guidance system. However, the European effort lacked the integration of Systems Management. As a result, five consecutive launch efforts failed in successively spectacular fashion, due largely to issues in communication and interface between each country’s contributions.

“We must be bold.”

Increasing collaboration between groups, teams, and project areas not only provides better contextual knowledge to everyone involved, it also serves to foster greater creativity, innovation, and transparency. Instituting this type of communication will be difficult. It was met with extreme resistance when initially implemented at NASA. Kennedy foresaw this in his moonshot: “We must be bold,” he said, “such a pace [of change] cannot help but create new ills as it dispels old.” Yet it worked then and it will work now. It will take great intentional efforts and increased coordination should we hope to replicate the success of the Apollo project, rather than the humiliating fate of Mercury Redstone One. When thinking about the challenges this type of communication entails, it’s easy to resist. Kennedy knew he would face detractors: “It is not surprising that some would have us stay where we are a little longer, and rest, and wait. But this country was not built by those who waited and rested and wished to look behind them.”

Dylan Mroszczyk-McDonald is part of the GovLoop Featured Blogger program, where we feature blog posts by government voices from all across the country (and world!). To see more Featured Blogger posts, click here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.