This is the second part of a post about BlueLight Camp, an unconference for Emergency responders, and those who work with them. The session I want to talk about this time was run by Farida Vis. Farida was a member of the team that analysed the 2.6 million tweets generated before, during and immediately after the riots that took place in the UK over the Summer of 2011.

Farida’s talk was filmed by John Popham, and broadcast live via Bambuser. It’s still available to watch online: Part 1 and Part 2. There wasn’t a large screen available in the room, so you probably won’t be able to see the slides Farida used. Happily, Farida has shared her presentation:

As the whole of Farida’s talk is available to watch online, I won’t try to cover it in detail and have just included a few of what – in my opinion – were the highlights. I’ve also included links to further information where appropriate.

Riots: Social media to blame?

In the immediate aftermath of the riots, different platforms were lumped together, and some prominent politicians even talked of ‘switching off’ social media in an attempt to prevent it from being used to incite or organise further disturbances.

In particular, there was considerable misunderstanding of the different roles of Facebook, Blackberry Messenger (BBM), and Twitter.

While not widely used for that purpose, some individuals did use Facebook to incite others to riot, and at least two men were jailed as a result.

Blackberry Messenger (BBM)

Blackberry Messenger (BBM) uses a high level of encryption which made it extremely difficult for authorities to intercept BBM messages exchanged during the riots. Blackberry agreed to cooperate with a Police investigation, as described in this Guardian article.

Twitter was an altogether different story, and the bulk of Farida’s session was devoted to discussing it.

Farida explained that she was particularly interested in the role of different ‘actors’, opinion leaders, and the roles that individuals had in creating or disseminating information.

Rumours

Farida was very interested in the temporality – or lifespan – of rumours.

Some rumours were born and disappeared almost immediately; many never made it beyond a small local area, whereas others were seized upon and became huge phenomena to be shared, repeated and embellished.

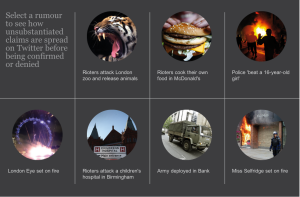

The Reading the Riots team identified seven of the biggest rumours, and have created some superb visualisations on the Guardian web site. If you haven’t seen them, they are well worth a look.

Farida observed that typically there’s lots of early repetition of a rumour, with people retweeting and adding their own comments. However, as time passes, individuals begin questioning, disagreeing with it and countering using logic. Some simply deduce that the rumour isn’t true. It’s not just organisations who dispel rumours – the ‘Twiterati’ play a really important role and can help calm down a situation very quickly.

Rumours and Zombies

In my previous post I referred to the story Andrew Fielding told whereby the filming of a Zombie movie caused all sorts of wild rumours to circulate. There could be a metaphor here:

- The movie generally starts with just the one Zombie, but very soon the bloomin’ things are everywhere

- They can be difficult to get rid of, until:

- Someone comes up with a way to stop them

- It all goes quiet, and they seem to have gone away

- Just when you think you’ve got rid of ’em, they pop back up again.

Unlike television, where an audience just consumes the broadcast, Twitter is a vast array of conversations, with people leaving and joining, going away, and returning again – this takes place in various different timezones across the world. Rumours therefore crop up again-and-again.

Farida’s advice to authorities trying to scotch false rumours is to keep on repeating factual messages, linking back to a reliable information source, preferably with evidence such as video or photographs.

That thing you heard, it’s not true

That thing you heard, it’s not true

That thing you heard, it’s not true

Farida then opened the session up for discussion and some useful points were made

- Lots of support for the need to repeat reassuring, factual messages

- Unless people are sure that others aren’t going to panic, they panic – You don’t panic buy petrol unless you think others are going to panic buy petrol.

- Example of local bloggers who spot a rumour and check with a trusted Police contact who then issues a statement, scotching those rumours which are untrue.

- Many councils retweet what the Police and Fire say (and vice versa) – Retweet the authoritative voice to make the most of all networks

- There’s great value in building a network of trusted sources – people who understand how to verify information.

- Don’t ever blindly retweet a rumour – take personal responsibility.

- Emergency responders (and other organisations) could benefit by drawing on individuals’ strengths:

- Some people are chatty – good conversationalists, so use for community engagement

- Others are good at analysis

- The ‘Twitter Junkies’ – could help by tracking rumours

- Farida advises dividing activities – don’t try to use one account for everything, or use just one person – they won’t have the capacity and no one is good at everything

Right Here, Right Now

Some people just happen to be in the right place at the right time.

They might only have a tiny number of followers, but they seem to “pop up, out of nowhere”, because of their location, by taking a picture or shooting a video to ‘capture the moment’.

The broom army image which was tweeted by Andrew Bayles had about 400k hits in just a few hours. Not only did he capture the moment, but he also shared it with some of the Twiterati – those with many followers. The iconic broom army photo was immediately retweeted by big hitters like John Prescott and Piers Morgan and then picked up by the mainstream press thereby making it to traditional TV and print channels as well.

A few more points

- Don’t place too much emphasis on sentiment analysis – people often struggle with sarcasm and irony and machines really don’t stand a chance!

- A tweet that mentions ‘burglary’ can be perceived as negative, even if it says “we caught a burglar”

- Interesting suggestion to ‘do a deal’ with Twitter to enable emergency services to use the promoted tweet facility in Twitter during a crisis

- Search is very interesting – what are people searching for at a particular time e.g. an increase in searches for Tamiflu might be an early indicator of flu

- David Lammy’s book: Out of the Ashes which looks at the causes of the riots and their broader implications is well worth reading

- Steph Gray has been working some excellent resources including the Social Simulator and The Digital Engagement Guide

In my previous post I mentioned investigating cross-posting between platforms. It’s worth reading the interesting article by Kim Stephens over on idisaster 2.0 that looks at this in some detail.

I’ve run out of time to finish this post off as I’d like to – I’d just like to repeat my thanks to Sasha Taylor, his fellow organisers, and the sponsors of BlueLight Camp for making it all possible.

The spirit of BlueLightCamp lives on and I was delighted to see Sasha’s recent tweet that he’s already on the case to organise the next one. There was also a #northernBLCamp session in Orkney last week as part of the excellent IslandGovCamp organised by Sweyn Hunter (@Sweynh and @IslandGovCamp). I was there, and intend to blog about that shortly.

This post originally appeared on my personal blog

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.