A borough gets notified that there will be no trash collection because the sole trash hauler is undergoing a staff shortage. A city finds itself unable to recycle all its plastics when the only sourced recycling contractor reaches full capacity. An airplane is idled for months when a replacement part becomes obsolete. A truck buyer cannot find a truck due to a chip shortage. Supply chains have become complex, but they are common to every process and every product. Yet, have the people who assemble them become expert in thinking of the future?

Governments that handle the day-to-day operations of society are finding that supply chains are unplanned. While not everyone has read SD-22 “Diminishing Manufacturing Sources and Material Shortages – A Guidebook of Best Practices for Implementing a Robust DMSMS Management System,” many people could benefit if policymakers had copies in their offices. The future is uncertain, and everyone from the loading dock worker to the highest elected policymaker must consider that we live in an imperfect world where you cannot assume that things will remain static.

The first step, as SD-22 notes, is to prepare. Preparation is always the hardest part because initial steps take the most energy. Preparing is the “what if” stage of thinking and requires people to look at their supply chains and ask more than basic questions. For instance, what happens if after an event, the energy or people who make supply chains happen can no longer function as they used to? What if everything just stops?

In some ways, it is the plot device of every scare story. But unlike the plot devices in movies and fiction books, the government employee has to think the opposite way: They must envision not a huge disaster, but the smallest of failures. The goal is to prevent minor failures from cascading into larger ones.

One way is to consider if the failure can be stopped. Can you mitigate it by having two suppliers and alternative purchases? Can a failure of one critical element of the supply chain be closely monitored so that before an impeding failure, a safety mechanism is triggered? In the case of personnel, can cross training prevent a systemwide failure?

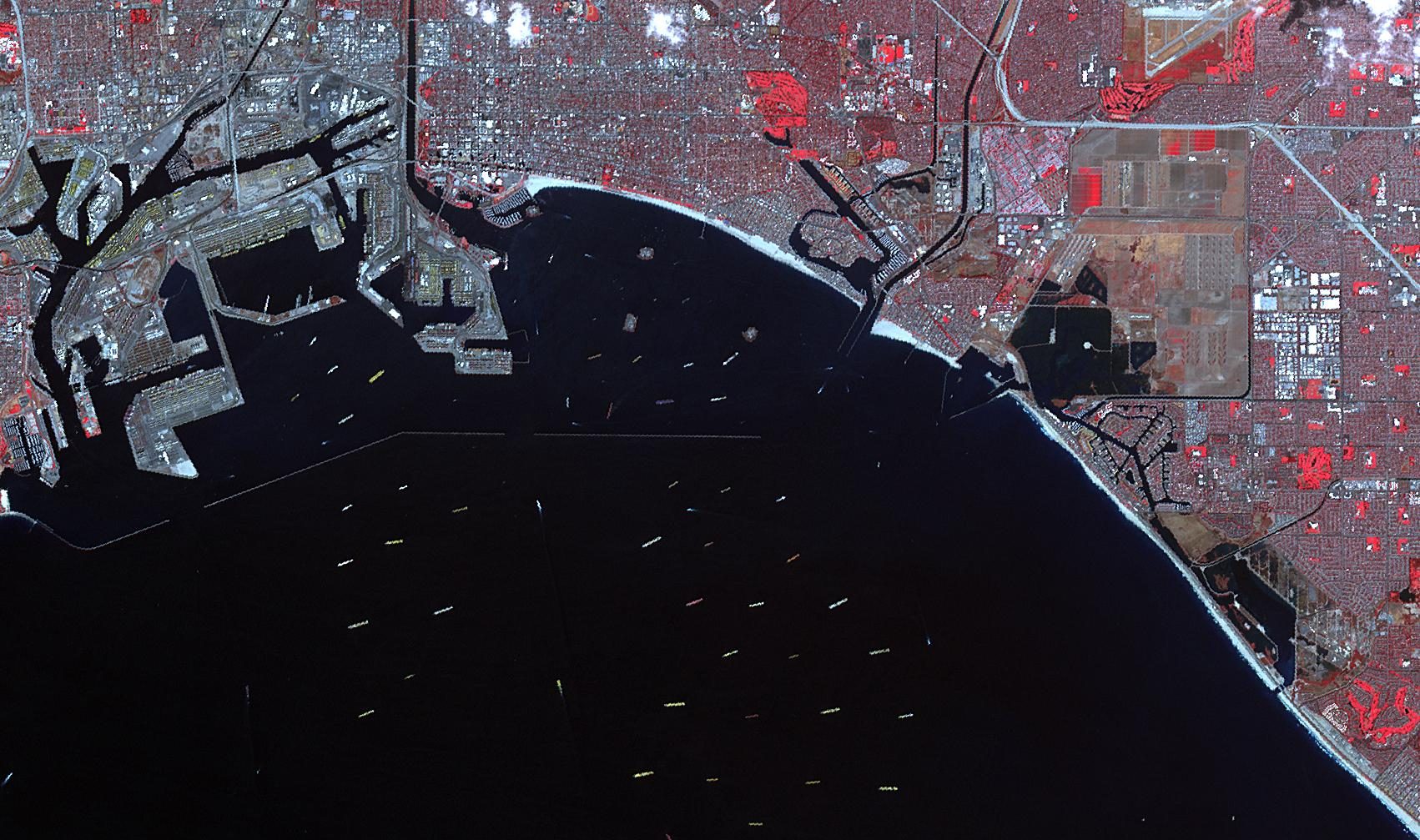

As governments deal with an increasingly complex supply chains to deliver goods and services, formal supply chain management becomes everyone’s task. No decision is too simple for anyone, and everyone must continually assess a supply chain’s health if changes take place. There is no reason to wait for a failure; carefully considering basic concerns today is in order. No one wants to be left out at sea waiting for the next wave to do their job.

Christopher Rabzak is the founder of CRXJEM Consulting LLC, a management consulting firm that focuses on technology companies. Chris received his Aerospace Engineering degree from Penn State University, and worked in private industry for Teledyne Ryan and Boeing, as well as government entities including NASA. Chris earned an MBA and a JD from Widener University. He founded CRXJEM in 2008, and works with tech firms, develops continuing legal education courses to help attorneys understand how technology works, and is a certified continuing legal education provider in Pennsylvania. He is currently forming an international advisory board for a growing tech company.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.