In another post, I mentioned how humbling and educational it was to be the project manager for our city’s new service request app. This app for web and mobile devices allows the community to report issues and request services from city government. Many communities have some sort of system where residents can get their needs met. Hopefully, it’s better than an “[email protected]” email, but you work with what you’ve got.

There are quite a few vendors who provide these 3-1-1 apps and systems. These companies do their best to design a platform that will work for most cities, with the most useful features. But every community has its own character, its own issues, and its own history and so will use its 3-1-1 app differently.

There are quite a few vendors who provide these 3-1-1 apps and systems. These companies do their best to design a platform that will work for most cities, with the most useful features. But every community has its own character, its own issues, and its own history and so will use its 3-1-1 app differently.How many governments invite the community to help select, design, and configure their systems?

For our citizen relationship management (“CRM”) system, we convened a number of testing sessions to gain feedback on the navigational structure. We had a lot of requests to build into the system, and we knew community members would have a challenge finding the appropriate type of request.

Testing for intuition

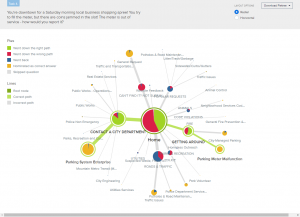

On a previous project re-designing the city’s entire website, our developer used an “information architecture testing tool” to understand how users expected the structure of the website to flow. Basically, it’s a way to give users a task (like “find information about the stormwater system”), let them navigate through a skeleton of the website, and track where their intuition led them. The results are presented graphically, which helps designers understand where the subjects would expect to find certain information.

We applied this idea to the navigation of our 3-1-1 app, testing the types of requests that we would offer in the app. When presenting to groups in our community, I would show several tools that the city offers, and then invite them to take the test to tell us where they would expect to report certain concerns.

Tree-testing tool results for “jammed parking meter”, showing that subjects traveled highly varied routes to report this issue.

Results and evidence

This testing helped us to identify challenges that community members had with our original design. While our natural inclination was to follow the city’s departments and divisions, we learned that residents’ intuition doesn’t follow organizational structure. Locating police complaints and other obvious law enforcement questions in the “police” category seemed to work, but other requests did not have clear connections to city departments.

Internally, it took some convincing to break the old department-oriented model. But data is a powerful tool to change minds. We worked with the front-line staffers who would receive these requests. We showed them how these decisions could reduce the amount of re-assignment and confusion around these requests. These became our advocates for a more topic-oriented decision.

The graphics showing poor performance in the testing, and the phrase “what was the resident doing when they had this problem?” became our guides to help move from department-centered design to designing the system based on the user’s perception.

Continuous improvement

The CRM system launched with success, and the navigation test is still in use today. We use it when community members file requests complaining about the system:

“Thanks for telling us that [specific complaint] doesn’t work for you– would you like to help us with the next round of navigation changes? Please take this test to let us know how you expect the system to work. We are always making changes, and we hope that you can help us make this system better with your feedback.”

The test continues to give us valuable feedback. For the small cost of the online test, we are able to involve our community in meaningful participation in the future of the very tool that gives them a way to report issues.

Even better, we are visibly trying to improve the system and we invite the public to help improve it.

Future community-involved service design

While the community didn’t have a role in the decision to use the vendor, the project team is very proud of the level of community participation in the configuration of the CRM system going forward. We are exploring the idea of involving the community in the design of other public-facing systems and processes going forward.

Whether implementing a service request system, conducting a public process, or creating a public board or commission, involving your public in the shaping of processes that affect them can give you insight into the public and create a defensible decision-making framework for offering services to your community.

Do you have examples of incorporating public participation in the design of digital services? I’d love to hear about them in the comments below.

Jay Anderson is responsible for digital engagement and public processes at the city of Colorado Springs. Jay holds an MPA from the School of Public Affairs at the University of Colorado – Colorado Springs, where he also serves as the Chair of the Dean’s Community Advisory Board. Jay focuses on the point of engagement between the community and its institutions, creating programs that give a voice to people who want to have an impact on their government.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.