This post is a follow-up to an unanswered question from GovLoop’s recent training, Critical Conversations. Want more topics and information like this? Make sure to register for our upcoming training summit in July, the Next Generation of Government Training Summit.

Read the following statements and decide if you agree or disagree with each:

- Most of my time is spent supervising my team.

- In order to get the job done the right way, I need to closely monitor the people I supervise.

- Budget first. All else is subordinate.

- My team needs me to tell them how to do their jobs.

- I could do the jobs my employees were hired to do better than they can.

- I like to be CC’d on emails so I can keep an eye on things.

- I can’t go on vacation without my team falling apart.

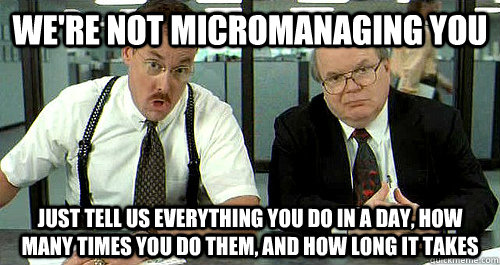

If you agreed with any of the above, congratulations! You’re probably a micromanager.

Dreaded by employees everywhere, micromanagers might mean well with their attention to detail, but they lack judgement about when to turn it on and when to lay off. The succubus of the workplace, micromanagers can drain energy, motivation, and morale. At their most extreme, micromanagers are the people in power whose insecurities cause them to hold back their employees’ productivity and happiness.

If you’re exhibiting the warning signs, here are ways you can put an end to your micromanaging:

Full stop

Quitting micromanaging isn’t much different than quitting any other socially unacceptable bad habit, like cutting your nails on the bus or watching the Kardashians.

If you’re still reading, you’ve taken the first step and admitted you have a micromanaging problem. The next step is to identify specific the things you do that make you a micromanager. If possible, have forthright conversations with your team to get their insight on what types of attention to detail are a hindrance or a help. Quitting is more likely to work if you get people you trust to hold you accountable, so ask a peer or mentor for their guidance.

Once you’ve identified your micromanaging tendencies, go cold turkey. Stop your bad habits by doing things differently. For example, schedule 15-minute mini meetings once a day or every other day to replace the many unscheduled “just checking in” interruptions. Make a list of the tasks you can delegate now, before you create a bottleneck of all the minutiae you were unwilling to trust someone else to do.

Once you’ve identified your micromanaging tendencies, go cold turkey. Stop your bad habits by doing things differently. For example, schedule 15-minute mini meetings once a day or every other day to replace the many unscheduled “just checking in” interruptions. Make a list of the tasks you can delegate now, before you create a bottleneck of all the minutiae you were unwilling to trust someone else to do.

Change your carrot

Economists and psychologists are still reeling over research showing that financial incentives can actually demotivate people and set them up to fail. Though we want to believe that we’re all special butterflies, decades of research shows most people’s behavior follows these truths:

For simple, mechanical, repetitive tasks, money can work as a motivator. But, most jobs are not simple, and that’s why financial motivations fail. Offering a higher reward actually leads to worse performance, especially when the work requires conceptual, complex thinking. Creative people especially are not best motivated by money.

This isn’t an excuse to underpay your employees. Rather, to get the best creative, thoughtful, or dedicated work out of people, the best approach is to pay people enough so they’re not thinking about the money and are instead able to focus on their work. Then, provide the four things that actually lead to better performance: fairness, autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

Dan Pink, author of Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us talks about motivation in this speech turned into an RSA Animate video:

Get out of their way

To lead, managers must support their employees to bring their best selves in the work they need to do. Many people, especially those with valuable talents and rare skills, want to be self-directed. They want to be trusted to reach the goal in the way they decide based on their experience and gut. Habitual micromanagers may not be able to do this every day, but try giving people autonomy for longer and longer periods of time and see if they perform better.

Effective managers also set employees up for success then get out of the way. When you give up micromanaging, you’ll have more time and energy for supporting your team. Use this newfound capacity to build access to the resources they need and knock down barriers between them and the goal. Increase the team’s chance of success by helping them identify and solve problems before they turn into a crisis. And, keep your team focused on the greater purpose that gives their work meaning.

Effective managers also set employees up for success then get out of the way. When you give up micromanaging, you’ll have more time and energy for supporting your team. Use this newfound capacity to build access to the resources they need and knock down barriers between them and the goal. Increase the team’s chance of success by helping them identify and solve problems before they turn into a crisis. And, keep your team focused on the greater purpose that gives their work meaning.

Lauren Girardin is a marketing and communications consultant, writer, and trainer. Find her on Twitter at @girardinl.

In a previous position I held where I unofficially oversaw a group of people I was told that I was micromanaging things and from the list above, I see a few things I was doing. The problem was that every time I would delegate something or ask someone to take on a new duty, the general response was that it was outside their job description or they would say ok but not actually do the work. I was unable to find the right balance and was not given the authority to ensure that the work was completed (all of our managers were offsite and rarely visited or paid attention). When I requested more authority I was told no and left for another position to get away from that negative environment.

Are there any suggestions on how to handle that kind of situation? How do you get coworkers to help with the workload when there is no one to hold them accountable?

I used to say that I had all the responsibility and none of the authority. Whenever something did go wrong, I was always the one that the bosses would get upset with and I really felt that micromanaging was my only option to ensure that I did not get into trouble.

Hi Dena, I might suggest you download our recent guide on project management: http://direct.govloop.com/projmgmtgov

There’s a section in there about how to manage people that don’t officially report to you that may be useful. I think that’s a very common issue in government — “all of the responsibility and none of the authority.”

Good luck!

I think it is important to recognize that micromanaging can be a form of workplace bullying, which contrbutes to an unhealthy and hositle work environment for employees. Although the optimum scenario is for a micromanager to correct the negative behavior, I think it is prudent that the supervisor of the micromanager watch and intervene, if the negative behavior persists and isn’t corrected, and put the micromanager on notice or make accommodations to move the micromanager to a position of nonsupervision. Should none of the above happen, what is an employee’s recourse if they are the ones being micromanaged?

Working with the micromanager’s supervisor or HR is definitely a smart first step. If that fails, you could try these techniques for managing up to help ease the micromanager’s anxiety: https://www.govloop.com/community/blog/5-proven-techniques-fine-art-managing/

And, here are tips for dealing with a micromanaging boss: https://www.govloop.com/community/blog/deal-micromanaging-boss/

I see this happening with leaders in my work environment, and these leaders have admitted that they are micro managers. I would like to share this article anonymously for their benefit. How can that be done?

I’m sorry to hear that you’ve got a case of micromanagers at your work! You could always print out this article and leave it on their desk or in their mailbox (leaving off your comment, of course). You could suggest to someone in HR or a senior leader that they share it with the team. Or neither of those are an option, there are ways to send an anonymous email—though I’m not the right person to recommend a website or technique for that.