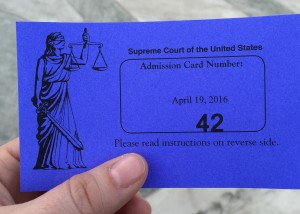

On April 19, I was fortunate enough to attend oral arguments at the Supreme Court for Universal Health Services v. Escobar. Although the facts of the case were tied to filings for reimbursement under Medicaid, the legal question at hand – whether the submission of an invoice to the government is an implied certification that the contractor has complied with all the material terms of the contract – is one of critical importance to all government contractors.

On April 19, I was fortunate enough to attend oral arguments at the Supreme Court for Universal Health Services v. Escobar. Although the facts of the case were tied to filings for reimbursement under Medicaid, the legal question at hand – whether the submission of an invoice to the government is an implied certification that the contractor has complied with all the material terms of the contract – is one of critical importance to all government contractors.

The primary reason the implied certification theory of liability makes many lose sleep is because of the False Claims Act (FCA), which allows for significant penalties – treble damages and fines of $5,500-$11,000 per claim – on a contractor who “knowingly presents, or causes to be presented, a false or fraudulent claim for payment or approval (31 USC § 3729).” In certain judicial circuits that accept implied certification, an invoice can be categorized as fraudulent if the contractor fails to comply with virtually any of the clauses or provisions in the contract.

While I will leave the nuanced legal discussion to the attorneys, especially when it comes to materiality, let me cite an example raised by Chief Justice Roberts that demonstrates how the theory of implied certification is currently applied by federal circuits covering the Washington, DC area. Generally, the Buy American Act applies to all contracts for supplies to be used in the United States with a value exceeding the micro-purchase threshold, as well as to the supply portion of services contracts when the amount of supplies exceeds the micro-purchase threshold [FAR 25.100(b)].

Chief Justice Roberts asked Malcolm Stewart, Deputy Solicitor General, if he would consider an instance in which a contractor provided $100 worth of foreign staplers as part of a larger $100,000 contract to be a false claim. Stewart responded that because “the government would be legally entitled to withhold payment or a portion of the payment in that circumstance, then that would be a false claim.”

Justice Breyer appeared concerned by the stapler example, noting that if it’s “just staples,” applying the FCA in that situation “would make the contractor responsible for having complied with every one of 40,000 regulations, the size of the room, size of the table.” Stewart equivocated a bit by explaining that this isn’t the type of situation where the government would seek to intervene, but you can see why the government’s interpretation makes contractors so anxious.

Chief Justice Roberts appeared the most sympathetic to contractors’ concerns, especially to the Petitioner’s argument that contractors are faced with a “morass of regulations” that are “full of cross-references…full of contradictions.” In contrast, Justice Sotomayor seemed the least swayed by the Petitioner. In her opinion, “it’s a very basic provision…when you say, I performed this service, that you performed a service in accordance with the contract.” Justice Kagan also questioned whether any terms of a contract could be immaterial – if they weren’t material, why were they included in the contract?

Chief Justice Roberts appeared the most sympathetic to contractors’ concerns, especially to the Petitioner’s argument that contractors are faced with a “morass of regulations” that are “full of cross-references…full of contradictions.” In contrast, Justice Sotomayor seemed the least swayed by the Petitioner. In her opinion, “it’s a very basic provision…when you say, I performed this service, that you performed a service in accordance with the contract.” Justice Kagan also questioned whether any terms of a contract could be immaterial – if they weren’t material, why were they included in the contract?

Neither side appeared to have a clear advantage at the close of oral arguments, in my lay opinion. Now all we can do is wait for the Court to issue its opinion, expected sometime in June. In light of Justice Scalia’s death, there is still a chance that the decision will not resolve the issue. Should the Court reach a 4-4 split decision, the judgment of the lower court will stand and the tripartite circuit split will continue for the foreseeable future.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.