This post is part of a series about the four envelopes that federal IT must “push” to restore public confidence in our capability to deliver superb citizen information technology services.

Having visited the project management envelope, the enterprise architecture envelope and the user experience envelope, we turn now to the collaborative development envelope – the cornerstone of expanded open source engagement and federal transparency. This envelope is as much philosophical as it is technological, although to implement it, strong technology will definitely be needed. In addition to the technology, this envelope could be most effectively implemented with changes to the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR).

The Philosophy

The open source community has been and continues to be a growing facet of software development. Major proprietary software developers such as Apple and Microsoft have, to one extent or another, begun to embrace that philosophy. When it comes to federal software development, there’s a discussion to be had about whose code it is: the government’s or the people’s.

National security issues aside, the collaborative development envelope argues for public ownership of code developed using public funds. Where national security is an issue, the presence or absence of data elements and functionality could disclose information that should not be generally known. There can be special exceptions there. But where national security is not an issue, the code for federal projects should be completely transparent to the public if faith in federal information technology is to be restored.

Viewed as a risk-reward proposition, we need to examine the purported benefits. The open source movement describes a number of them: better quality, higher reliability, more flexibility, lower cost and an end to predatory vendor lock-in. The vendor lock-in for federal development is often the preference to extend or award follow-on development to the original developer. Where open source development is involved, disintermediation eliminates that lock-in. But getting to that point requires a strong technology foundation on an unmatched scale of the $80+ billion annual investment in federal IT.

The Technology

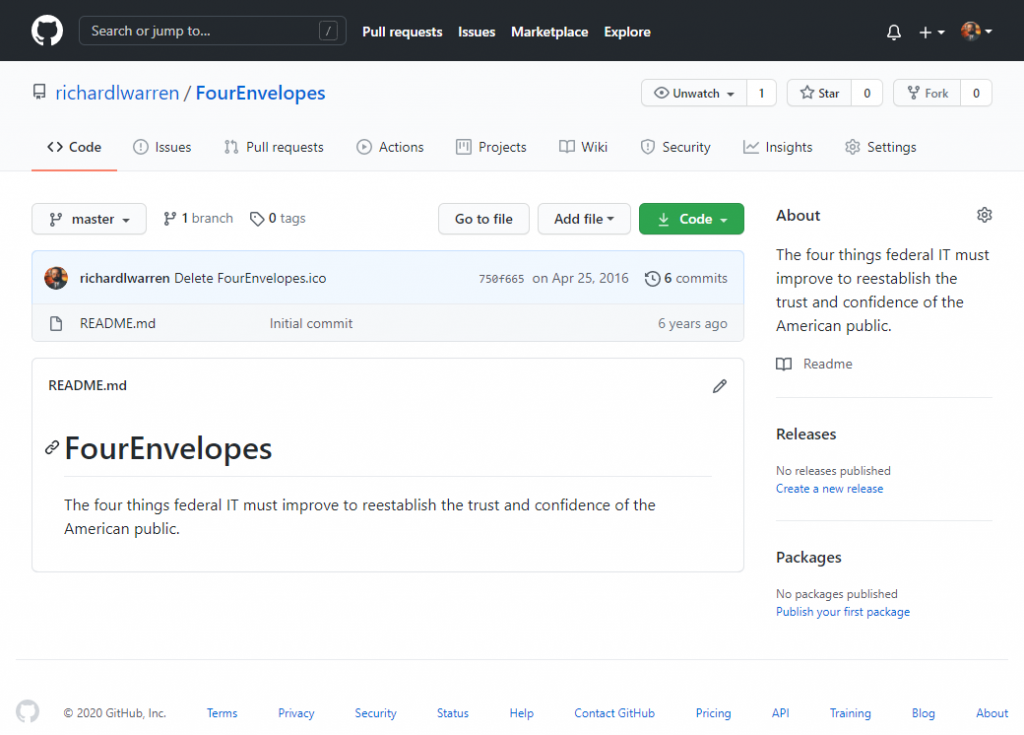

The mechanisms of open source code management are well understood and widely practiced using tools that are readily available. GitHub would likely form the foundation for the collaborative development envelope with one repository for each of the federal departments and agencies. Within that repository, each project could be individually listed and have multiple branches as required for those with an interest in actually providing alternative code, functional and structural improvements, or higher-performing optimization.

GitHub repositories work with projects and within project branches. The implementation for the collaborative development envelope is to have each department own their own repository and segment that repository by projects.

Add-in tools such as SonarQube (hopefully without the poor implementations detailed this week) could be used to test submitted code in an automated way that would support the scale needed to push this envelope. Enough languages are supported so that even COBOL code could be scanned in this manner, supporting the oldest coding likely to be refreshed by the federal government.

The Federal Acquisition Regulations

For this envelope to work, there needs to be an incentive for both the original code development contractor and the open source revision and improvement of that code. Many, if not most, development contracts are “time and material” (T&M) contracts that conform to the Federal Acquisition Regulations subpart 16.6. What is missing from the FAR, but needed for this envelope to truly succeed, is an incentive contract type for T&M contracts that has an award fee associated with it.

T&M contracts reflect a high degree of uncertainty on the part of the government and contract for a level of effort and material cost recovery approach. There are no incentives for this contract type, and this type of contract can only be used when no other alternative exists. That’s usually the case with software development contracts. What this type of contract doesn’t guarantee is the quality of work delivered.

Various approaches to determining deliverable quality exist and an independent verification and validation (IV&V) is often used when the scope of the investment is so large and complex that governmental assessment of the quality is problematic. As it applies to this envelope, IV&V could become the mechanism that monitors the GitHub repository and assesses the quality of the code offered by a reviewer. Using that assessment, an award fee could be set compensating the original developers in the same 50-100% of the fee to be awarded. As an added aspect, the difference between the award fee and the total award fee amount could be distributed to the open source contributors or donated to a Combined Federal Campaign charity of their choice.

What the government gets out of this is an improvement in the quality of the developers and development. T&M contracts are fiercely competitive on the labor categories and rates that are proposed. This has the side effect of not hiring the best developers because of cost factors. The open source collaborative development approach compensates for this and rewards the best contract developers accordingly. If the best code is delivered by the contract developers, they will be the ones who benefit the most from this envelope, so the incentive is to simply deliver the best possible code and not just punch the clock for T&M purposes.

Wrapping Up and Moving On…

So, those are the four envelopes, with the concluding collaborative development envelope – the cornerstones of best development practices in the federal public sector and the payoff envelope in the series. Government development projects have traditionally been close-to-the-vest efforts. This lack of public disclosure has resulted in disasters like healthcare.gov and others that are less well known. The Project Management Institute estimates that 12% of IT investment is wasted because of poor performance. The collaborative development envelope addresses that performance and provides an incentive to achieve better solutions with a completely transparent approach.

What we’ll look at next week is how this might all be translated into reality, nurtured, and supported as the envelopes become entrenched in federal lifecycle management.

A retired naval officer, Richard Warren entered public service in 2009. He holds the PMI Project Management Professional, Risk Management Professional, and Agile Certified Practitioner certifications and currently serves on their Federal Sector Executive Roundtable and other PMI executive roles. He also holds the Federal Acquisition Certification in Program and Project Management at the expert level. He was a founding member of the U.S. Digital Service at the request of the Federal Chief Enterprise Architect and the Obama administration.

This was an interesting read, and you really drove it home with examples like healthcare.gov and other less known outcomes snafus (for lack of a more apt descriptor). PMI’s estimate of 12% is also striking! I’m looking forward to reading next week’s piece.