After polling centers close on election day in Saint Louis County, Missouri, each site’s two supervising staff members place an iPhone in the ballot box, secure it, and travel by police escort to the county’s Board of Elections office.

The iPhone uses geographic information system (GIS) technology to deliver real-time location data that is displayed on a map. Eric Fey, the county’s democratic director of elections, monitors each box’s location as he waits with his colleagues to receive the night’s final votes and announce election results.

In the past, Fey would know when ballot boxes were on their way but would not know their precise locations. Meanwhile, he would field phone calls from candidates, county personnel, and journalists who wanted updates on results.

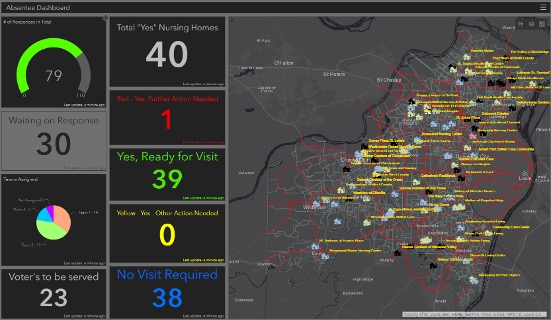

Now, Fey and his team have a dashboard that takes away the uncertainty — the iPhones that track ballot boxes work in concert with other GIS-powered tools to provide a complete operational picture throughout the election cycle. A suite of web maps and mobile apps keep officials, candidates, and constituents updated throughout. Then the cycle repeats.

Moving From Paper to Smart Maps

The most populous county in Missouri, Saint Louis County is home to nearly one million people with more than 700,000 registered voters who have to vote for hundreds of officials — from senators to the school board.

“It’s our job to make sure people get the correct ballot,” Fey said. “This is a big challenge in election administration. Everyone knows who they want to vote for, for president or governor. But in larger jurisdictions, when you get down to state representative and county commissioner, if someone gets the wrong ballot, they might not even know it.”

Previously, Board of Elections personnel were using colored pencils to redraw district lines on paper maps based on new census data. If these boundaries are redrawn incorrectly or aren’t accurately translated into a voter database, errors occur and elections have to be rerun, which is costly for municipalities and their constituents.

Now, maps are available on the Redistricting Hub at the Board of Elections’ website. The resource aggregates all county districts, outlines their boundaries, and shows any recent changes. Most redistricting processes happen every ten years, but if boundaries need to be redrawn, the maps must reflect changes immediately. With the Redistricting Hub, these changes can be made and communicated to constituents and stakeholders, including politicians whose district locations and makeup may have shifted.

Optimizing Election Preparation

Recently, new laws in Missouri made it easier for people to vote. Voters can now visit any polling center — instead of an assigned location — or vote as absentees. A Polling Place Lookup tool and an Absentee Voting Lookup tool highlight satellite sites and calculate driving times to locations where voters can drop off their ballots. Voters can also explore their ballots ahead of time with the Saint Louis County Sample Ballot Lookup tool.

Fey’s team used GIS technology to determine where to place new sites for early voting. “Data from the November 2022 election showed us where people were voting. We could also see that there were some dead zones where we didn’t have a polling center,” he said.

The Board of Elections is also responsible for distributing voting equipment to nearly 300 polling centers across the county. Prior to implementing GIS technology, warehouse employees would sit down with paper maps and draw out delivery routes. Now, workers can optimize delivery routes to find the quickest routes considering traffic conditions and the shortest to minimize travel distance.

Setting Expectations

On election day, GIS apps keep county officials and constituents informed in real time. Voters use the Polling Place Lookup tool to monitor wait times at each location. A volunteer counts the voters in line and logs the number in ArcGIS Survey123, which then populates on the web map. The line tracker is popular because it saves people time — on Election Day in 2020, 365,000 people used it.

Fey and his team monitor polling place wait times to anticipate problems. If a device malfunctions or another error occurs, Fey can locate a mobile team member closest to the issue and dispatch them to troubleshoot.

“Situations can develop rapidly on election day and GIS gives us the ability to visualize what is happening,” said Rick Stream, republican director of elections and Fey’s counterpart. “With these tools in place, election days seem somewhat less fraught than they used to be when we could only guess at what was happening in the field.”

Looking Forward

Using data, maps, and mobile tools throughout the election cycle adds transparency to the county’s processes, which matters when allegations of foreign disinformation campaigns, voter fraud, or voting machine security arise. When Fey needs to answer a question, he has authoritative data to point to.

After each election, staff members aggregate and analyze all the collected data and review their processes. If a certain polling place is popular, Fey can allocate additional resources to that location for the next election.

Fey’s office compiles a biennial report filled with maps after every general election. The reports help officials visualize where they did and didn’t receive support and show the large amount of data the Board of Elections collects and synthesizes.

They are ahead of the curve. According to the National States Geographic Information Council, the majority of states are in the early stages of integrating GIS into their election processes. By focusing on hiring GIS personnel and investing in the tools they need, the Board of Elections created a culture where people use location data to solve problems. “It’s these little improvements,” Fey said. “Every little piece builds on something else.”

Christopher Thomas is the director of government markets at Esri and a founding team member of the Industry Marketing Department. Prior to joining Esri in 1997, he was the first GIS coordinator for the City of Ontario, California. Thomas frequently writes articles on the use of GIS by government.

To learn more about how state and local governments can foster greater trust in elections with GIS, visit esri.com/en-us/lg/industry/government/elections-gis-brochure.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.