If you’re planning to go car shopping any time soon, you’re likely in for some sticker shock. Last year, low supply led to an 11.8% price increase for new cars and 37.3% price increase for used cars. This price increase was driven by a decline in production — a decrease of 3 million cars in North America during 2021 — due in large part to the global shortage of semiconductors.

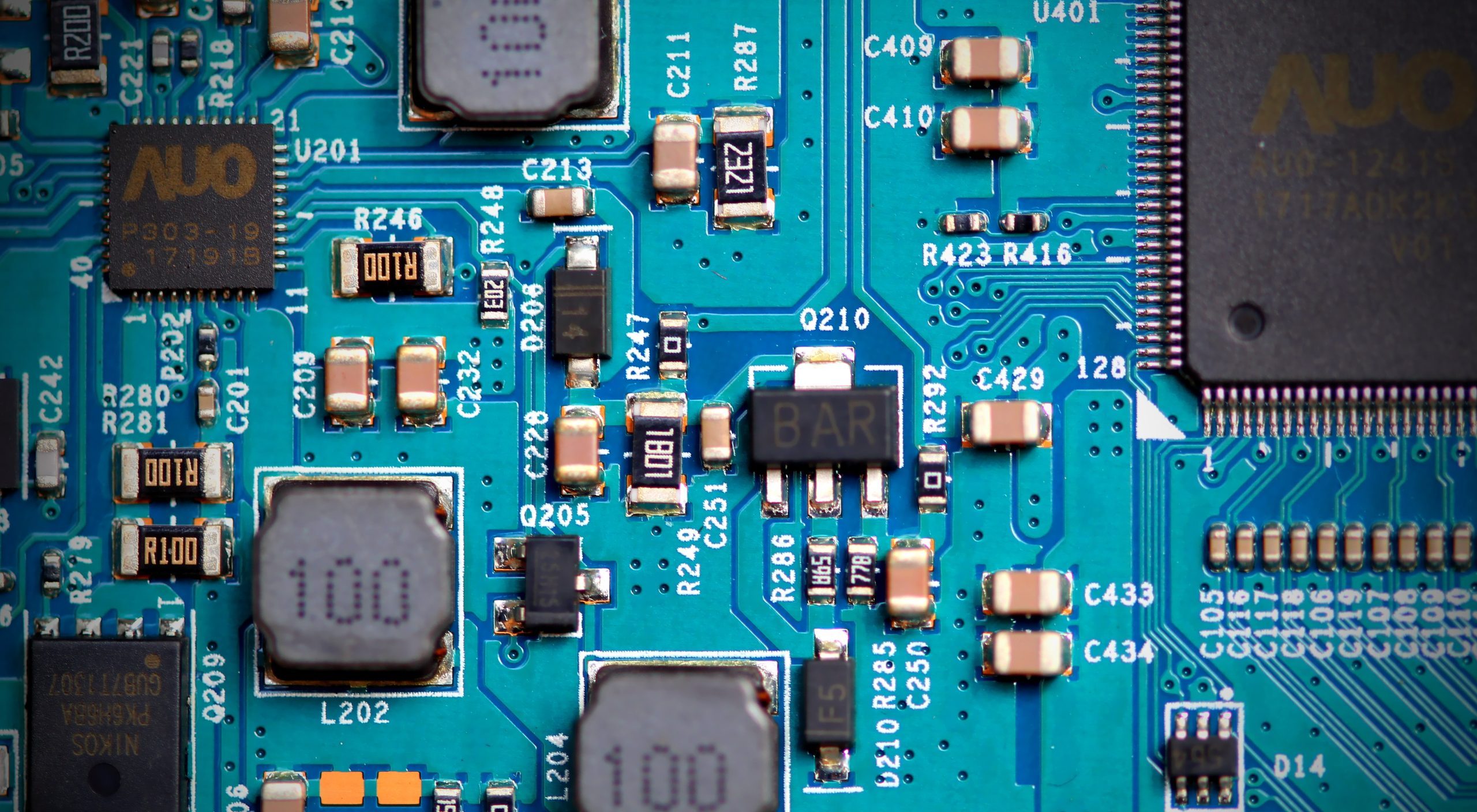

Semiconductors, known more commonly as microchips, are miniscule parts that hold massive importance to nearly all of our modern technology. From smartphones and computers to household appliances and medical equipment, most of our gadgetry would be useless without microchips. Without a steady supply of these tiny components, production of goods that rely on them can grind to a halt. In 2020, that’s exactly what happened: Industries that relied on semiconductors experienced challenges getting the supply they needed, production slowed, and the market for a wide range of goods went haywire.

Beyond hitting consumers in the pocketbook, the shortage of semiconductors is a threat to our national defense. Fighter jets, missiles, and other advanced weaponry rely on semiconductors as much as the electronics around our homes do. The more advanced a piece of technology — a stealth fighter or a spacecraft, for instance — the more and more semiconductors likely require to process massive amounts of data.

Further complicating the issue, there is an ongoing shortage in the critical minerals used in the production of not only semiconductors — which require lithium and cobalt — but many other technologies in increasing demand, including many “green” technologies. Solar panels, advanced batteries, and wind turbines all rely on critical minerals. Their names are a mouthful: germanium, manganese, scandium, niobium, tantalum, vanadium, and so on, an alphabet soup of materials in limited supply, many of which the United States is forced to import, often from strategic competitors. If the U.S. needs to rely on Chinese supply of these minerals to build new fighter aircraft, the situation is obviously less than ideal.

As technologies progress and demand grows for semiconductors and critical minerals alike, these and other future shortages will only continue to threaten both our modern conveniences and our national security. Action is needed.

Finding lessons in crisis

There are numerous lessons to be found within the semiconductor and critical minerals shortages, and the past several years have provided a harsh education. Whether it’s a shortage in production of a technical component, the availability of raw materials, or whatever weakness is inevitably exposed in a future crisis, leaders must learn from these situations now in order to reinforce their organizations for the challenges to come. Through participating in the examination of these issues in my role at the Government Accountability Office, I have observed two broad lessons that together focus on building resilience.

1. Search for the Achilles heel

In Greek mythology, Achilles was the most fearsome of the Greek warriors, a nearly invincible figure and a hero of the Trojan War. Despite his legendary strength and skill in battle, he met his end due to a wound to his one point of weakness — his heel. The semiconductor and critical mineral shortages have rightly caused a great deal of nervousness across our nation that the absence of something as small as a “chip” could cripple our economy, our quality of life, and our national defense. These concerns are warranted, and require our attention.

We cannot allow the existence of single points of failure in our organizations. It’s unlikely that very many of us stop to consider the miniscule components of the technology we rely on, but what if we remove that little part, or that quietly productive employee? When we overlook which specific cogs we have come to depend on, we accept a risk that the absence of the smallest thing could cripple even the strongest organization.

No matter what field we work in, our success or failure should not depend upon one part, one person, or one process.

2. Always seek collaboration

In a recently published report, GAO highlighted improved collaboration as one of several potential approaches to reduce risks and mitigate the effects of the semiconductor shortage. This collaboration was of the broadest kind: between federal agencies, across borders with our international partners, and even with strategic competitors like China.

Semiconductor production is a truly global endeavor, and issues in its supply chain send ripples around the world. No single nation possesses all of the resources and raw materials needed to satisfy the diverse, growing, and constantly evolving demands of modern technology. Collaboration here isn’t just a potential option, it’s a necessity that cannot be ignored. Our progress, and indeed our problems, will only continue to reach across agencies and borders, and we must learn to harness the increased potential of a collaborative mindset.

What these lessons have in common is that they both contribute to reinforcing the overall resilience of an organization against a future crisis, whatever form it may take. Our recent report identified increased resilience in our supply chains as a potential focus for federal policy action. GAO defines resilience as an ability to prepare for anticipated choke points, adapt to changing conditions, and withstand and recover rapidly from disruptions. This kind of resilience applies beyond the supply chain or federal government: Resilience can be a positive aspirational goal no matter our organization or mission.

Candice Wright is a Director in GAO’s Science, Technology Assessment, and Analytics team. She oversees GAO’s work on federally funded research, intellectual property protection and management, and federal efforts to help commercialize innovative technologies and enhance U.S. economic competitiveness.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.