There are periods throughout the economic cycle when fiscal austerity is needed, and there are periods when fiscal spending is needed. A lot of mainstream literature (aka “the media”) attempts to take a black-and-white stance on government spending and its ideological repercussions. Today the debate of government spending seems to be taking place in a different stadium of thought given the unique circumstances of a ‘global pandemic’, but in the eyes of certain actors, the debate remains the same.

There are periods throughout the economic cycle when fiscal austerity is needed, and there are periods when fiscal spending is needed. A lot of mainstream literature (aka “the media”) attempts to take a black-and-white stance on government spending and its ideological repercussions. Today the debate of government spending seems to be taking place in a different stadium of thought given the unique circumstances of a ‘global pandemic’, but in the eyes of certain actors, the debate remains the same.

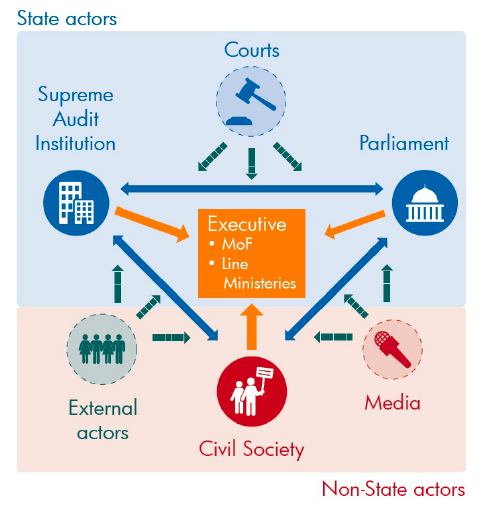

Credit agencies are among the most important non-state actors involved in the checks and balances processes of public administration and public budgets. Their role is essentially to audit the governance and institutions of the public sector according to specific budgetary principles in order to rate their fiscal health. There are several guides of budgetary principles that determine these ratings –the OECD defines the following criteria in their 2015 Principles of Good Budgetary Governance:

- Budgeting within fiscal objectives

- Alignment within medium-term strategic plans and priorities (MTEF´s)

- Transparency, openness and accessibility

- Participative, inclusive and realistic debate

- Capital budgeting framework

- *And others…

Governments at all levels – federal, territorial, municipal…etc. – acknowledge the importance of these credit agencies as a means to SIGNAL credit worthiness to internal and external investors. Some institutional investment organizations often require minimum rating levels in order to execute debt clauses and obligations under different loan programs, including the IMF and the World Bank.

Case Study

A case study of the importance of credit agencies is the case of Barranquilla, Colombia. In 2008 the incoming mayor Alejandro Char was elected over a banner of “Fiscal and Financial Healing” and a mandate to correct a municipality that had billions of Colombian pesos (COP) in debt and a deepening fiscal deficit. The new administration latched on to a series of fiscal laws and rules, set by the federal government, that had been designed to support subnational governments to improve their fiscal health. These laws included the Medium-Term Fiscal Framework Law 813 of 2003 which established a federally mandated Medium-Term Fiscal Framework (MTEF); Debt Reform Law 550 of 1999, which incited the federal government to act as a liaison and guarantor in negotiations to restructure public and private outstanding debts governments; and Public-Private Partnership (PPPs) law 1508 of 2012 which promoted PPPs under a transparency index.

By latching on to these laws, Barranquilla was able to transform its economy in ten years, and eventually in 2017 received a AAA national credit rating from Fitch Ratings as well as BBB international rating – both being rectified in 2018 and 2019. This stance has made the city one of the most prosperous financial cities in the country, giving it quick and reliable **access to capital liquidity at market prices for infrastructure development and continued fiscal improvements.

Times of Crisis

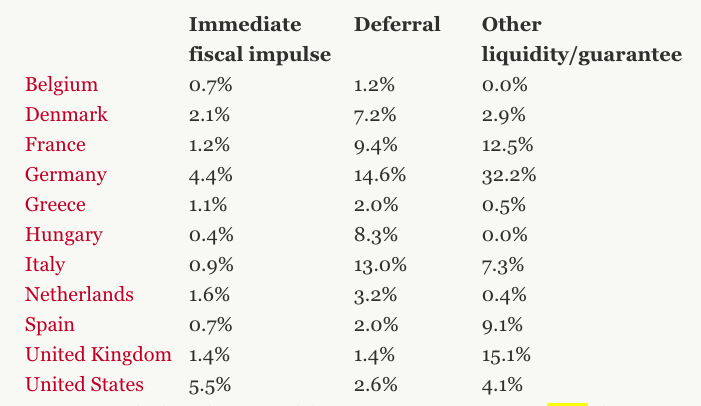

On the other hand, there is also a question of when credit agencies should demonstrate leniency and self-reflection. Currently, many governments are preparing some of the largest fiscal expenditure programs ever designed to combat the economic repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Among the different programs being proposed are expenditure bills in the way of temporary universal income subsidies, payroll substitution welfare for businesses, tax deferrals, and others. The scale of these programs can be exemplified in a few examples that demonstrate the proportion (%) of GDP of these packages:

***https://www.bruegel.org/publications/datasets/covid-national-dataset/

In terms of Colombia, where a package of around 50-60 billion pesos is being discussed, which would represent about 5-6% GDP, Fitch has already jumped the gun and downgraded Colombian rating to BBB which is just one level above investment grade. Many academics and economists are debating whether the pressure to adhere to these ratings, and their structural influence with international capital funds, may be delaying necessary spending programs being proposed.

Colombia is a government with high levels of informal labor markets, high levels of poverty, a migration crisis from Venezuela which can accelerate social fissures, and a high dependence on an oil industry which is being battered by international disputes in the other side of the world. Under these circumstances, it is important that the government act quickly and aggressively in the same way other governments have done so, and that credit agencies demonstrate lenience in their circumstantial judgment of their fiscal frameworks.

Whether or not the credit downgrade of Colombia was justified in the context of the global economic earthquake is debatable. Furthermore, its bare influence in decision-making (and non-decision-making) of governments should also be taken into consideration as leaders scramble to balance economic prosperity, social stability, and the spread of a pandemic. Perhaps credit agencies should prepare conditional contingencies to adjust their credit analysis with a comparative perspective in times of global, or regional, crisis such as this one. The adjustments to do so would better prepare governments to plan accordingly on how to respond during black-swan events as well as maintain as level a playing field as possible.

Enrique Jose Garcia is a GovLoop Featured Contributor. He was born from Cuban parents and was raised in Venezuela until moving to the U.S. to attend university. He has spent most of his career as an entrepreneur in the beverage sector, both in the U.S. and in Cambodia, and most recently started a Master’s at the London School of Economics in Public Administration and concentrating his studies on Social Entrepreneurship. He currently spends his time between London and Colombia and writes for a few publications on economics and entrepreneurship in Latin America.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.