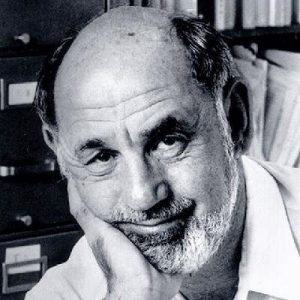

When studying fiscal budgeting, one of the first lessons they teach you is the law of incrementalism. First proposed by Aaron Wildavsky, a scholar in the field of political science and budget theory in the 1960s, the concept of incrementalism in budgeting refers to the comparative nature of yearly budgets as an alternative to the stand-alone perspective of budgets. In other words:

When studying fiscal budgeting, one of the first lessons they teach you is the law of incrementalism. First proposed by Aaron Wildavsky, a scholar in the field of political science and budget theory in the 1960s, the concept of incrementalism in budgeting refers to the comparative nature of yearly budgets as an alternative to the stand-alone perspective of budgets. In other words:

“Budgeting is incremental, not comprehensive. The beginning of wisdom about an agency budget is that it is almost never actively reviewed as a whole… Instead, it is based on last year’s budget with special attention given to a narrow range of increases and decreases.”

– Aaron Wildavsky (1964)

The topic of incrementalism has come to light in recent weeks amidst the intense market volatility being seen around the world in response to the Coronavirus scare. (Granted, last week the volatility was further amplified by the oil industry price war between Russia and Saudi Arabia, but this supply shock was also directly related to the coronavirus.) For several weeks, we have been hearing endless debates, theories, and hypotheses about the response of the financial markets, the impact to certain industries, mainly travel and oil, and the expectations for fiscal and monetary responses by governments.

With so much confusion going around at every level of society, and from every sector, I have found it interesting to see the amount of weight being given to short-term and medium-term expectations at the expense of long-term expectations. Again and again, we are being told the same thing by the academic, economic, and health experts; that the economic impact of COVID-19 can be seen as a “Black-swan” event that has no substantial basis on economic fundamentals other than putting into question the valuation ecstasy that markets have been living with during the recent 11-year bull-run (in the U.S.). The virus will undoubtedly have an economic impact, but it is expected to be short-term with a horizon of between 6-9 months as A) the summer months put pressure on the flu-like Coronavirus, and B) Rapid technological ingenuity ramp up vaccination responses to the virus.

And yet we have still witnessed markets that have been freaking out with historical selloffs and rebounds just because the word “uncertainty,” which is the least favorite word of financial markets, has been thrown around like a ping-pong ball.

The interesting thing to take away from this volatility is the sheer myopic nature of financial markets. Along with the drop in financial equity markets, we have also seen a massive wave of liquidity transfer towards government bonds and other “safer bets” at the expense of stock markets. This has, in turn, resulted in trillions of dollars being transferred into treasury debt accounts (very little to corporate debt) and away from corporate equity accounts. As a result, several governments are now preparing for very specific bailout options targeting the most vulnerable industries and their employees. Chances are that in Q3-Q4 of 2020 no government had properly anticipated their fiscal budgets to reflect this Hollywood-like scenario.

This experience should serve as a lesson to governments and industries around the world when preparing their yearly budgets and designing fiscal contingencies to possible “black-swan” events. Governments, much in the same way as traders, have to leverage their financial risks and hedge against potential volatility swings. With markets, consumers, and citizens becoming more myopic (it seems) by the generation, expectation horizons and sensitivity ranges are contracting despite the fact that volatile inducing-events and global competition have been decelerating aggregate economic growth for several years now.

These knee-jerk reactions have shown us, yet again, that markets are being driven by short-term expectations. It is ironic that, in their fear of the word “uncertainty,” markets are choosing to ignore the certainty of long-term growth. The law of incrementalism holds the underlining assumption that in the long-run economies grow and therefore budgets grow. That does not mean that there is no room for short-term fluctuations, dips, and “crashes” in between. Governments would do well to collaborate with the academic sector and the private sector to communicate the contextual realities of economic volatility so as to moderate the emotional responses of liquidity-creating institutions such as financial markets.

We should acknowledge how the coronavirus scare has simply been the existential excuse that U.S. financial markets have been looking for to stabilize the self-driven valuation orgy they have been enjoying for several years now, and accept that “this too shall pass” as the law of incrementalism continues to drive our economies over the long run. Nevertheless, wherever he may be, Aaron Wildavsky must be looking at us with a nervous grin in the hope that we can digest the law of incrementalism, and the lessons of these events, before the next big correction hits us in the head.

Enrique Jose Garcia is a GovLoop Featured Contributor. He was born from Cuban parents and was raised in Venezuela until moving to the U.S. to attend university. He has spent most of his career as an entrepreneur in the beverage sector, both in the U.S. and in Cambodia, and most recently started a Master’s at the London School of Economics in Public Administration and concentrating his studies on Social Entrepreneurship. He currently spends his time between London and Colombia and writes for a few publications on economics and entrepreneurship in Latin America.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.