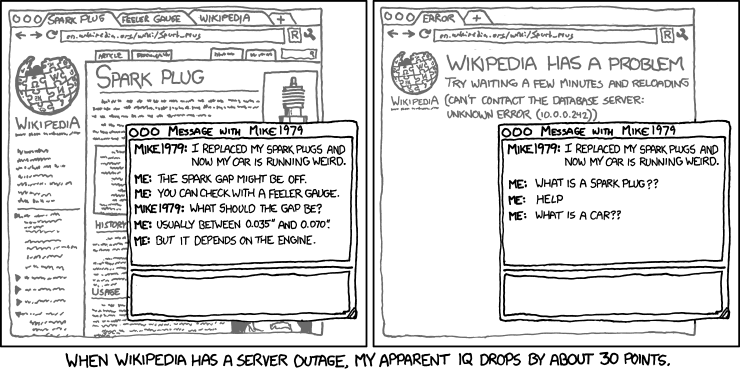

I noticed the phenomenon XKCD describes above in a recent trip outside the states to Uzbekistan, via Munich. When I touched down in Germany, to my surprise the airport didn’t have wifi and data roaming was $20 a megabyte. With prices more fitting of truffles than data and no internet outlets like I had seen in Denmark, for the next 12 hours connectivity would be a luxury for emergencies only.

So what’s the problem? If you’re only in Munich for 12 hours, why do you need internet? Go out, have a beer (sold here in liters), and see the city. Well, expecting to be able to get online one way or another, I had arrived in Munich with no plans or information, ready to make it up as I went. I knew that the airport was about half an hour from the heart of the city, but I didn’t know how to get there, or even where “there” was. I wasn’t even sure how to reach transportation or get around the sprawling airport. Uzbekistan would be even more extreme, with internet only available through the wifi at the first hotel I stayed in in Tashkent at the very beginning of the trip.

Was I the world’s most helpless traveler? Perhaps, but more likely, our hyper-connected world had changed the way I think and I had grown too used to my information age superpowers. With a smartphone and laptop, I was used to having the World Wide Web and the wealth of information it represents at my fingertips whenever and wherever. Years ago, I would have at least looked up the layout of Munich airport before I had gone, or printed out a map. I had intended to meet a friend in town who had to cancel so I didn’t have a plan, but the analog Alex would have hedged his bets with a guide or list of things to see. He would have familiarized himself with public transportation.

Now that we’re always online, I didn’t think to do that because the paradigm of the digital age is we can find out whatever we want. All the answers are one Google search away. Consider how this has changed our thought process. “I wonder…” used to be the beginning of a rhetorical question. Now, it’s followed by a search that, in a minute, either answers the question, gets you closer, or shows you what others have thought before you. You can be arguing with a friend while walking down the street and then, with your smartphone, fact check him in an instant to settle the dispute. We now have access to a massive repository of information and knowledge and, as my example demonstrated, we’ve internalized it into our decision-making and reasoning as part of our consciousness. In other words, we’ve become cyborgs.

Research is just one example. Web 2.0 and social networking brings a man-machine connection into our social lives. By the time I was seeing incredible splendor in Uzbekistan’s legendary Bukhara and Samarkand, once known as the Pearl of Islam, I made sure to take pictures so that, through Facebook or email, my friends could see what I’m seeing. Technology had augmented the very act of seeing, taking in, and thinking about sights and experiences. Even more “sci-fi” is that some of these friends I had never met in real life. They knew me through Twitter or my blogs, extensions of my identity through technology. I’m far from alone here. More and more often, I hear people saying in the real world that they would “like” something if it were on Facebook. At events, friends and colleagues talk among themselves but at the same time tweet developments to their followers. Virtual communities and virtual friendships accessed through technological mediums that redefine how we interact with and think about the world. Looks like we’re social cyborgs as well.

Technologists often talk about augmented reality, but our reality has already been augmented by the information technology around us. Technology is now developed to live in that cyborg space, such as WayIn which lets you get feedback from your friends online on what you’re seeing in real time. Other augmented reality technology to perform visual searches based on pictures taken from a smartphone (what’s the name of that cathedral? What do people think of that restaurant?) seem to constantly be on the horizon.

All of this gee-whiz technical optimism comes also with a caution. In Munich, it took me several hours to readjust to an analog world. I remembered that there were maps without GPS, and with a little practice, they could be just as useful. Even foreign metro systems are meant to be user-friendly, and with a little trial and error I bought a ticket and got off at the first stop that looked important. Upon stepping out of the subway, I bumped into a free tour that also happened to be in English and had a great day in a new city. Yet I was lucky, and this still took time.

What happens when your enterprise adopts a new technology, such as a cool collaborative platform, and everyone internalizes it in the way they think about work and problem-solving? Abandoning one platform and switching to a new one can be disruptive. If it’s critical to getting the job done, losing a tool you’ve mastered can be like losing an arm. And if that tool went down, how easy would it be to finish the project on Google Docs? On a broader level, could your enterprise get by without internet or, even more basic, computers, until a problem, disaster, attack, or failure, cyber or kinetic, was resolved? Making sure mission critical tasks do not fail during an IT worst-case scenario is important yet often overlooked until some crisis arises because, just like I did abroad, we take technology for granted and fail to see how much we’ve made it a part of ourselves like our eyes and ears. That’s why experts like Robert J. Bunker in Red Teams and Counter Terrorist Training suggest simulating working under such failures occasionally. China’s PLA, for example, runs drills on operating despite an EMT blast that wipes out electronics. Technology that enhances our capabilities to work efficiently, learn more, and, in the end, think, is a good thing, but like everything else, it can be vulnerable. We must, therefore, maintain resilience and agility for when change or failure inevitably strike. We may be cyborgs, but we’re not robots.

Related articles

- Even Cyborgs Need Somebody Sometimes (commercekitchen.com)

- WayIn Adds Another Dimension to Polling (ctovision.com)

- 10 Amazing Augmented Reality iPhone Apps (mashable.com)

WOW! I have a totally different plan for foreign travel. I only bring my cell phone to call my family can pick me up when I return. I immerse myself in the cultre, music, food, people because that’s the reason I’m visting Foreignlandia. I have fabulous expereinces breaking Ramadan fast with a Sudanese at the top of the Eiffel Tower, conversing with Indigenous and Spanish people in Peru, disscusing Alcoholics Anonymous with the man I shared a table with at an English pasty shop, and miltary service with a female bobbie. Electronics would only interfere with my immersion and dilute my expereince.

You’ll like this:

Wow again. Thanks for sharing T Jay. Where is the balance between connection/instant access to you or the net and pondering?

Definately not a solid line dividing the two, more like a continuum that is constantly being rebalanced.

According to a poll on GovLoop’s Facebook, GovLoopers agrees that we are basically already cyborgs. 13 respondents said they would be lost without their smartphones, while only 4 said they’d rather not deal with them and keep it simple!

Plato talks about the creation of cyborgs with his discussion of writing. Because it makes knowledge extrinsic, rather than intrinsic, to humans, writing destroys knowledge, as there can be no knowledge outside of the human mind. Google is only the 21st century manifestation of Plato’s papyrus.