![]()

I live in the City of New Haven, CT (#gscia). I am reading a super famous book about cities called City by Douglas Rae. It is one of the best books I have ever read.

It has 12 chapters. This is a 12-blog post series about each chapter. Here are the other posts in the series: Chapter One, Chapter Two, Chapter Three, Chapter Four and an extra.

This post is on Chapter Five: Civic Density.

—

When I was a sophomore at Yale, I got involved in The Future Project.

At the time, it was a super exciting, new education initiative connecting young people with high school students based around a mutual passion. I was able to work intimately with high school students on projects that we cared about in the communities we knew. At the same time, I began making friends with people who lived in New Haven (and fell in love with one of them!) — giving me an increasingly larger stake in the city. And now, two years after graduating, I’m happy to have stayed.

The Future Project was unique because it gave Yale students the opportunity to meet New Haven high school students and residents on equal ground. It didn’t center service; it centered friendship and accountability.

—

In Chapter Five of City, Rae talks about a past example of Yale students and high school students sharing spaces together.

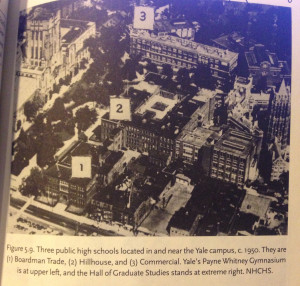

Until 1955, three city high schools were located on Yale campus. They stood in between Yale’s Payne Whitney Gymnasium and the Yale Hall of Graduate Studies: 1. Boardman Trade; 2. Hillhouse; and 3. Commercial High (now known as Wilbur Cross High School).

Here’s a picture from Chapter Five of the three schools on Yale Campus. Payne Whitney is the building to the far left, the Hall of Graduate Studies is to the far right.

Here’s a picture from Chapter Five of the three schools on Yale Campus. Payne Whitney is the building to the far left, the Hall of Graduate Studies is to the far right.

As Rae says:

“This concentration of educational activity must have all but compelled contact between Yale students and the high school students — and served as a constant reminder that Yale was for better or worse an urban institution.”

-Douglas Rae, Chapter Five of City

Rae argues that the location of these high schools may have impacted the rates at which high school students applied and were admitted to Yale. In 1907, 36 New Haven High (now known as James Hillhouse High) students were admitted to Yale University.

Now, New Haven’s public high schools stand a significant distance from Yale’s campus, and the numbers look different: In 2016, zero James Hillhouse High students in the New Haven Promise Scholar program — a well-known scholarship program covering tuition at a Connecticut college or university — were admitted into Yale.

In fact, of the 307 Class of 2016 Promise scholars, only three were admitted into Yale overall. And of those three, only one was from a New Haven Public School (one from Wilbur Cross High School; two from a charter school called Achievement First Amistad High). This means, potentially, that of the Class of 2020 at Yale (1,373 students), less than .001% of students are from New Haven.

I’m missing some data:

- From the past: The only 1907 Yale admissions data I have is Yale’s applicant decisions into their Sheffield Scientific School — not the rest of the university. There may be more local students who were admitted in other parts of Yale in the early 1900s that weren’t recorded.

- And from the present: The only 2016 Yale admissions data I’ve been able to find is through the New Haven Promise Scholarship Program. The program, however, has been working intimately with New Haven Public Schools since 2011. Therefore, it may be unlikely that there are many local high-school students who attend Yale without going through New Haven Promise program.

Yale is a major funder of the New Haven Promise Scholarship Program, potentially in order to position more local high school students as future Yale undergrads. In addition, there are numerous Yale-affiliated programs that support Yale students’ service activity within New Haven. These actions have powerful outcomes in the lives of both kinds of students.

Thinking about my experience with The Future Project, I believe that New Haven high school students need more and different things too. We feel driven to apply to programs only when we can actually envision ourselves being a part of them. New Haven high school students need to not just be provided service or funding from Yale, but to feel like Yale belongs to them. Trust needs to be built before more New Haven students feel like Yale can become part of their own identity. They need to meet Yale students who aren’t just helping them, but meeting them on equal ground.

Investing in programs that encourage local students to apply to Yale by meeting Yale students has long-term benefits. University and college towns across the country care deeply about “retaining talent” — about keeping young energy and ideas in the city after graduation. And the best way to retain talent locally is to cultivate local talent — to educate the local students who already live in New Haven, whose families are here, and who are most likely to stay here after college graduation.

Caroline Smith is part of the GovLoop Featured Blogger program, where we feature blog posts by government voices from all across the country (and world!). To see more Featured Blogger posts, click here.

Great piece! two small thoughts: Hillhouse also deteriorated academically; it used to be a top-ranked school in the nation. Also, reading this article, I think about Yale’s program allowing city high schoolers to take courses on campus for free. I think that may be the best example of your idea. Sadly Yale has cut back on the program quite a bit; in my kids’ day, you could take multiple courses per semester.