We all know the saying, “a picture is worth a thousand words.” In government, this saying holds especially true for imagery. Images help us analyze and derive information that shapes policies, educates us about our environments and informs decisions that affect millions of citizens’ lives.

Imagery analysis methods like change detection help provide critical data for environmental monitoring and natural resource management. Beach erosion, melting ice caps and forest fires are types of change detection analysis that can be done to offer a new view into how the land has transformed over time.

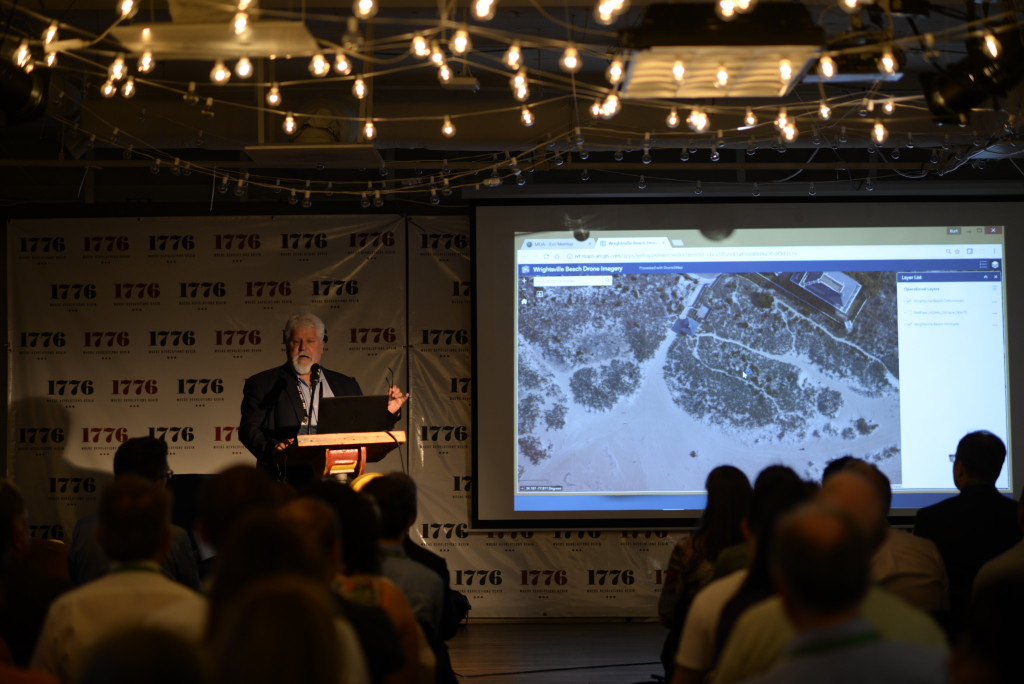

These topics were the focus of this month’s GovLoop and Esri meet up: Using Imagery for Visualization and Analysis. Presenters from Esri, MDA Information Systems and Chesapeake Conservancy shared insights on best practices for using technology to automate imagery analysis from drones and small satellites, how change detection helps shed light on the effects of natural and manmade events on our planet and more.

Kurt Schwoppe, Imagery Business Development at Esri, has seen firsthand the evolution of satellites and aerial photography over the past decades. But despite the advancements, gaps reamin. Schwoppe calls this the gap of micro-geographies. “The world is filled with small places in need of powerful maps,” but there is a gap in the imagery collection process, he explained. “That is where the advent of drones is going to be a game changer.”

He highlighted a pilot program with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that involved drones. To address the Corps of Engineers’ concern about beach erosion, Esri teamed with the organization on a project to assist with the beach nurturing. Schwoppe showed the level of detail the drone picked up on Wrightsville Beach in North Carolina. It collected elevation data in high resolution that could even detect tire tracks on the sand.

That data was paired with imagery from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to assess the beach before and after Hurricane Matthew made landfall on the east coast.

This is just one of many examples showing how drones can be used to solve issues in micro-geographies. “It takes a platform to do this,” Schwoppe said. The issue with some of today’s readily available mapping technologies is they don’t include data collected by an organization, particularly the agencies and companies that cannot publicly share imagery data. But Esri gives them the ability to add their data to its platform.

Using Esri’s imagery capabilities, organizations such as MDA Information Systems and the Chesapeake Conservancy have been empowered to compare historical and modern imagery over time and perform what’s called persistent change monitoring, or the ability to highlight areas of new construction activity by isolating changes that persist over time.

Jon Dykstra, Vice President of Research and Development at MDA Information Systems showed how human activity, such as construction, can be monitored over broad areas and used for regulatory enforcement, intelligence tip-offs or other uses. These capabilities are supported by Esri technology hosted in the cloud.

Jeff Allenby, Director of Conservation Technology at Chesapeake Conservancy, uses Esri capabilities to help reduce nutrient and sediment pollution, monitor the impact of client change on critical habitats and detect changes across large landscapes. He made clear that the Chesapeake Conservancy isn’t interested in just creating compelling imagery.

“A pretty picture is great, but what are you going to do with it?” Allenby said. The organization wants to make data and maps accessible to other entities, counties and anyone who needs them.

The focus is getting the right practices in the right place, at the right scale, at the right time and making sure they are working together, he said.