The Federal Information Technology Acquisition Reform Act (FITARA) is misnamed, says former Federal Chief Information Officer (CIO) Tony Scott. But that’s not to suggest he thinks the law has failed to transform the way government goes about its IT investments; the title, he suggests, is just too narrow.

“The only thing I’ll complain about FITARA is I think it was misnamed just a little bit,” Scott said Tuesday at ACT-IAC’s Executive Leadership Conference in Philadelphia. “While it had a little bit to do with acquisition, really it just had to do with good practices, good governance.”

As it nears its five-year anniversary in December, FITARA has left a mammoth impression on government IT today – in far more than just the way that agencies buy technology.

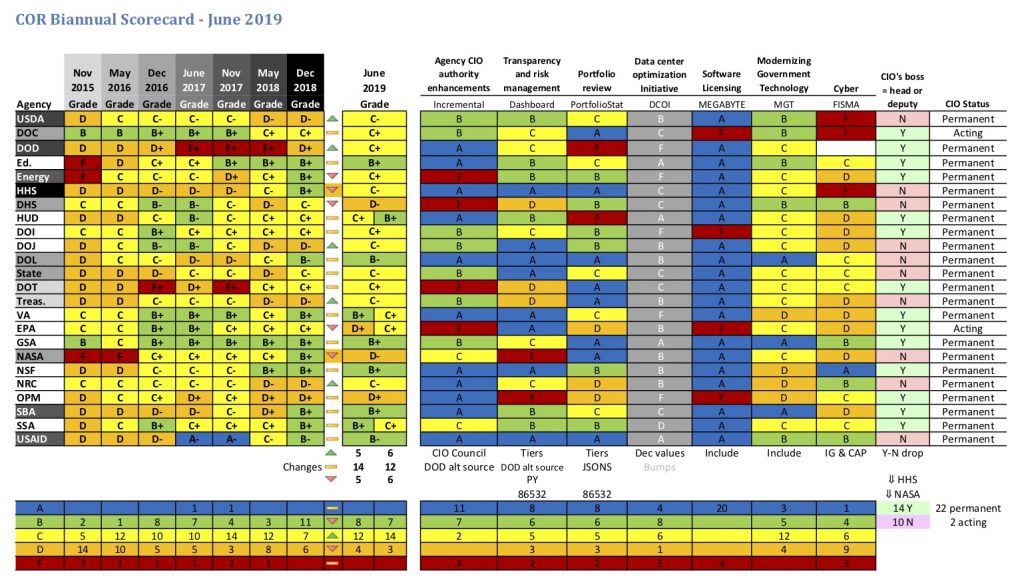

FITARA spawned the tradition of House Oversight and Reform Committee IT scorecards, key Office of Management and Budget memos (OMB) and governance boards throughout agencies. OMB memos 15-14, 16-12 and 16-14 are responsible for implementation plans, self-assessments and maturity frameworks that have defined FITARA’s five-year existence. Scott piloted memo 15-14, a significant document following FITARA, after assuming his position just months after FITARA’s signing into law.

As Scott joined a panel of current CIOs and FITARA founding fathers, the conversation naturally turned to what worked and what hadn’t.

Summarily, self-assessments proved to be unreliable – an expected vice of self-glorification – while mandates for maturity models and congressional evaluations put meat on the bones of IT needs within agencies.

The FITARA Enhancement Act of 2017 and the Enhancing the Effectiveness of Chief Information Officers Executive Order, both signed into law by President Trump, gave CIOs better visibility and control over the costs of their IT portfolios.

Maria Roat, CIO of the Small Business Administration (SBA), credited FITARA for helping her agency transform its IT. SBA, which has notably axed hardware purchases in favor of cloud, moved from an F rating to a B+, the joint highest score for any agency. The maturity model, she said, is a way that she continues to judge her progress.

While Roat noted that positive and involved conversations with her chief financial officer (CFO) and chief human capital officer assisted in SBA’s digital transformation, others noted that FITARA helped to get them on the same page with executives.

Panelists offered anecdotes where bad grades on a scorecard could prompt action from CFOs. Leading to greater IT spend control at the hands of CIOs, FITARA elevated chief information officers’ position in agencies.

“It began with FITARA because that’s when the rest of the agency started to pay attention to get stuff done,” Renee Wynn, CIO of NASA, said.

FITARA’s work is far from done. Although updates have been published, five years in, panelists agreed that tweaks are needed to modernize the modernization act.

The scorecard, at times, falls short in considering the unique circumstances of agencies and the realities of working with the many regulations and demands passed down, panelists said.

Federal Deputy CIO: It’s Time for FITARA to ‘Evolve’

Working within the system, Wynn recommended having direct conversations with OMB and Congress to explain what is plausible and what is not, sharing the agency’s vision of its best way forward. She also said that running from these orders, which are designed to improve the technology standing of agencies, is not the way to go.

“The assumption that you need new resources to do something that’s necessary is a fallacy,” Wynn said.

Labor Department CIO Gundeep Ahluwalia boasts some of the best scores – with five A’s of a possible seven– because of reaching an agreement with Congress to transform expiring funds into working capital funds. The workaround is one to admire, but one other agencies might struggle to emulate.

Wholesale improvements are needed now with FITARA, Scott said. Scott, who now works in the private sector, said he notices four missing items in calculating these scores and modernizing agencies: customer service, technical debt, architectural debt, and policy and process debt. Technical debt refers to legacy systems, architectural debt refers to antiquated models and charts of workflow and integration, and policy and process debt address outdated organizational standards.

Margie Graves, Deputy CIO of OMB, said that she doesn’t think anything is missing, but it is time for FITARA to “evolve.” As the CIO Council goes about redesigning the measures, it will take into account customer satisfaction and citizen service as standards. She remarked that the current “one-size-fits-all” model of FITARA evaluations could welcome more case-by-case measurement standards, as well.

Changes could be on the way, inspired by what agencies have requested. Graves noted that agency applications to the Technology Modernization Fund (TMF), a competitive loan system that offers agencies more funds to modernize IT, have offered valuable visibility into the modernization challenges that agencies face.

If FITARA is changing, the mission is not. No matter the name, panelists clarified, it’s about far more than acquisition.

“The C-suite works together to make sure we reach the end game, and the end game is not that we modernized IT,” Graves said. “It’s that we improved citizens’ experience[s].”