This blog post is an excerpt from GovLoop’s recent guide, How You Can Use Data Analytics to Change Government. Download the full guide here.

No police department has the manpower to be everywhere at all times. Even in a city the size of Norcross, Ga., which spans only 6.5 square miles, that’s still impossible.

Some 16,000 people call Norcross home, but nobody knows how many come into the city every day for work. “The problem that we have is, for such a small area, we have quite a number of armed robberies and burglaries,” said Bill Grogan, Captain of Support Services for the Norcross Police Department. “I don’t have the resources to cover 6.5 square miles, 24 hours a day, seven days a week.”

Like many other law enforcement agencies, the department has relied on heat maps to pinpoint hot spots for crime. “It’s old school, in my opinion,” Grogan said. “It’s too convoluted for the average officer to understand where he or she needs to be.”

Plus, these maps can only give officers a historical view of where crime has occurred. That kind of data is fine for viewing trends over time, but for officers patrolling the streets, the solution is reactive — not proactive. “We wanted to find something to lessen the number of property crimes,” Grogan said. But the department wasn’t searching for just any solution. It wanted to invest in resources that could proactively show officers where crime is most probable.

In 2012, a new police chief took the reins and shared his vision of using technology to make everyone’s job easier, not more cumbersome. About a year later, both Grogan and Police Chief Warren Summers stumbled upon an article about the use of predictive analytics in law enforcement. “We wondered if it was possible to predict crime,” Grogan said.

That question was put to rest on the first day the department rolled out predictive policing software in 2013. Officers nabbed someone wanted for burglary, and a few weeks later they caught burglars breaking into a home. Those are just a few of the success stories.

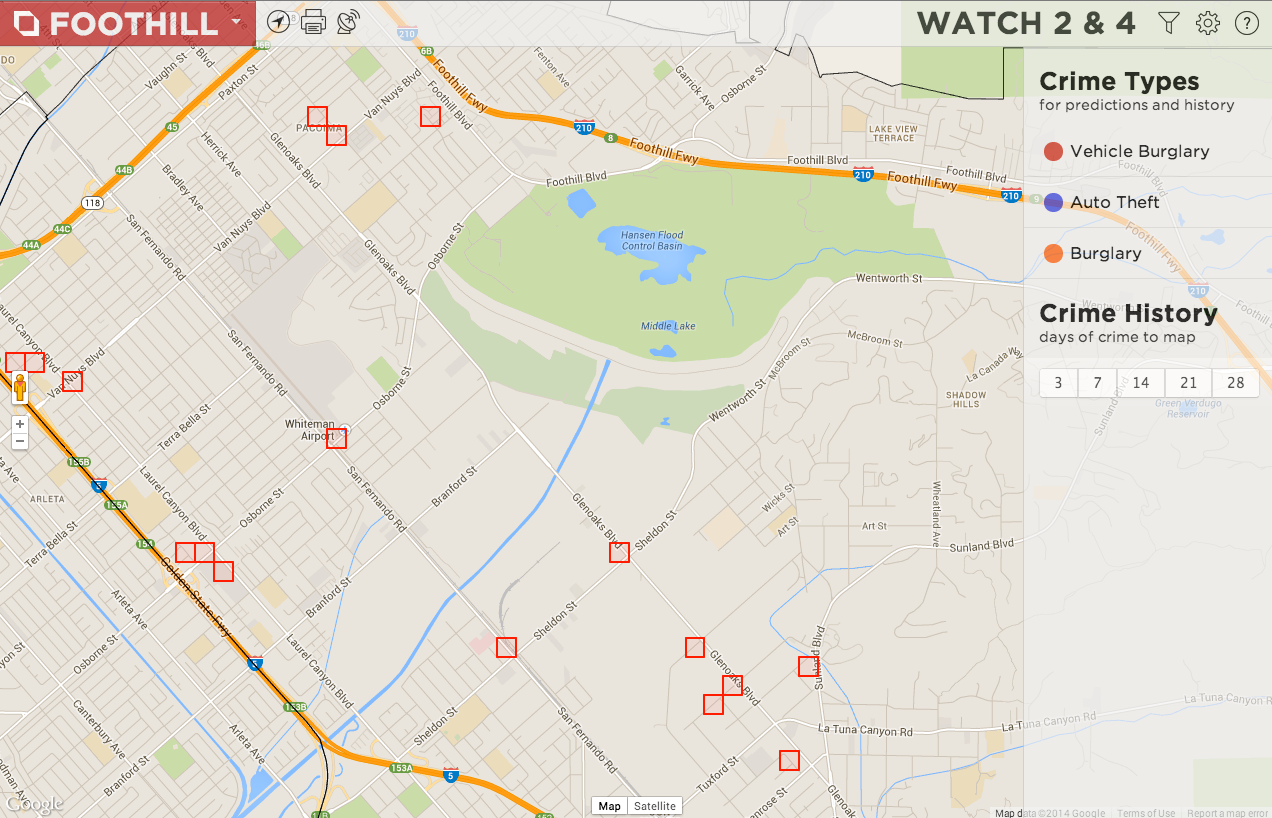

This is how it works: The company that provides the software gets real-time data feeds and historical data from the department’s records management system, including the type of crime, where it happened, and the date and time it occurred. Using algorithms and very fast data crunching, the software generates “prediction boxes” that show officers the most probable location where a crime might occur.

“This is not a crystal ball or ‘Minority Report,’” said Grogan, referring to the science-fiction movie in which police used technology to arrest murderers before they committed crimes.

The data that officers receive from the software tool is in real time. When they first come in for their 12-hour shift, officers log on to their computers to view the prediction boxes — eight red boxes, each representing a 500-by-500-foot area, spread over a map. Officers can zoom in on the boxes, which might encompass an apartment building, a gas station or a roadway.

All of the department’s police cars are equipped with GPS, and supervisors can monitor the amount of time that officers spend in the boxes. If officers spend too much time in the boxes, they’re neglecting other parts of the city. The goal is to spend a little more time in the prediction boxes than in other areas because that increases the chance of preventing crime, Grogan said. Those boxes change for every officer, depending on the time of day, the most recent crime data, and the type of crimes the department wants to target.

It took more than a year to get everyone on board with the software, Grogan said. It was easier to get new officers to use the software because they had no other routine coming in to the department. But veteran officers were another story. “Police officers do not like change. We prefer things go like they’ve been going,” he said. In addition to tracking the extent to which officers monitor their prediction boxes, the department also tracks whether or not officers use the software.

Grogan said officers have become increasingly good at recognizing areas where there’s a higher probability of crime. The technology is easy to use and requires very little training, which helped boost adoption.