In the past decade, the concept of user experience (UX) in government IT has gained widespread acceptance and moved into the mainstream. Long considered an afterthought or not even worthy of consideration, UX has emerged as a principal metric for the effectiveness of systems and applications.

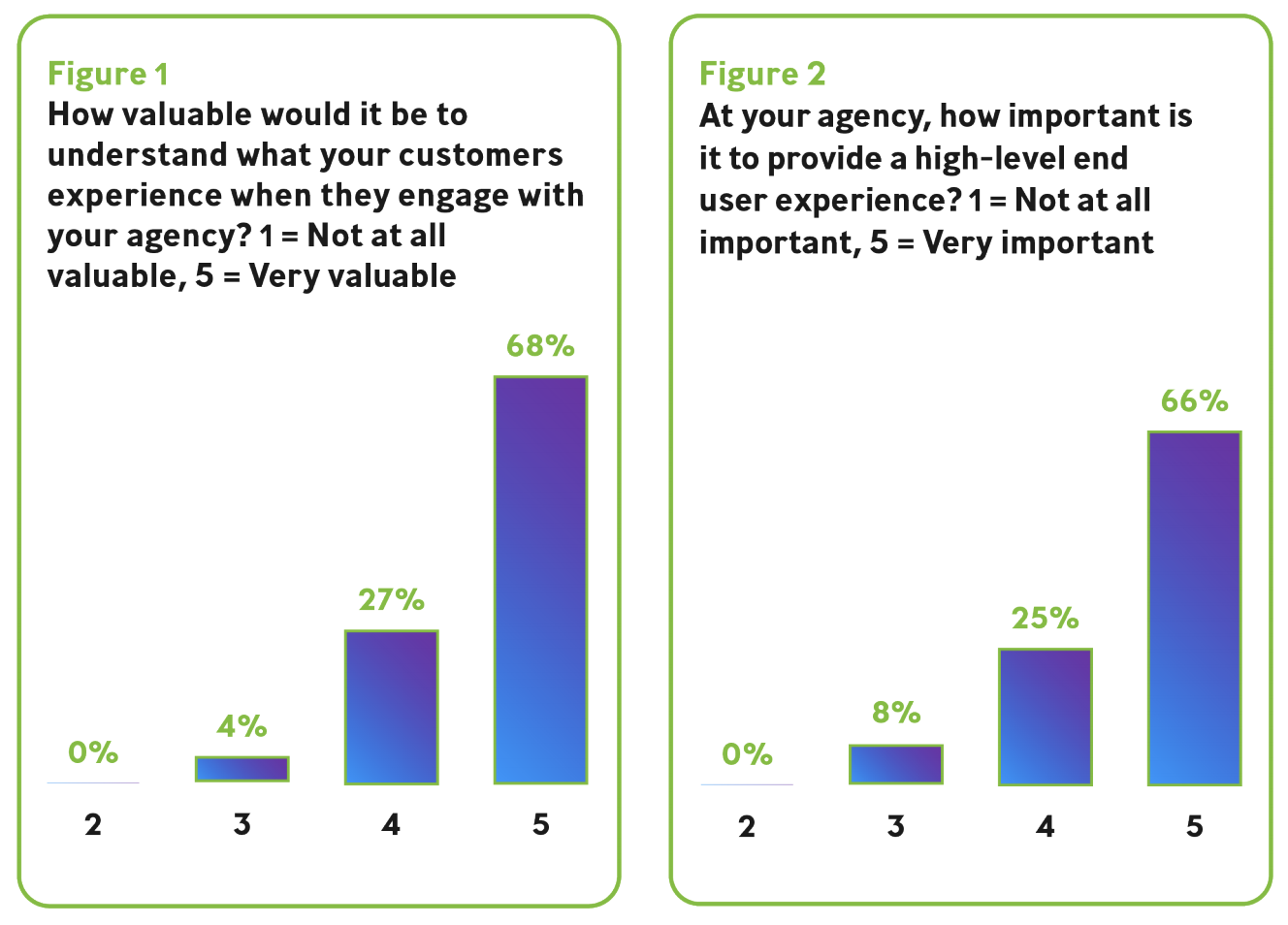

Almost seven in 10 respondents said that understanding customers’ experience would be “very valuable” (see Figure 1), while more than 60% said that their agencies consider providing a high-level end-user experience to be “important” or “very important” (see Figure 2).

Such sentiments would have been inconceivable until fairly recently, said Willie Hicks, a Senior Application Performance Engineer at Dynatrace, a technology company that specializes in software intelligence. Hicks remembers trying to interest engineers at a federal agency in the value of UX management about a decade ago. They weren’t buying it.

“‘You know, user experience doesn’t really matter because it’s not like [the user] is going to another agency,’” Hicks recalled one of the engineers saying. That notion of government agencies serving as unique providers of services and therefore inoculated against poor performance reflects a mindset that Hicks has seen change in recent years.

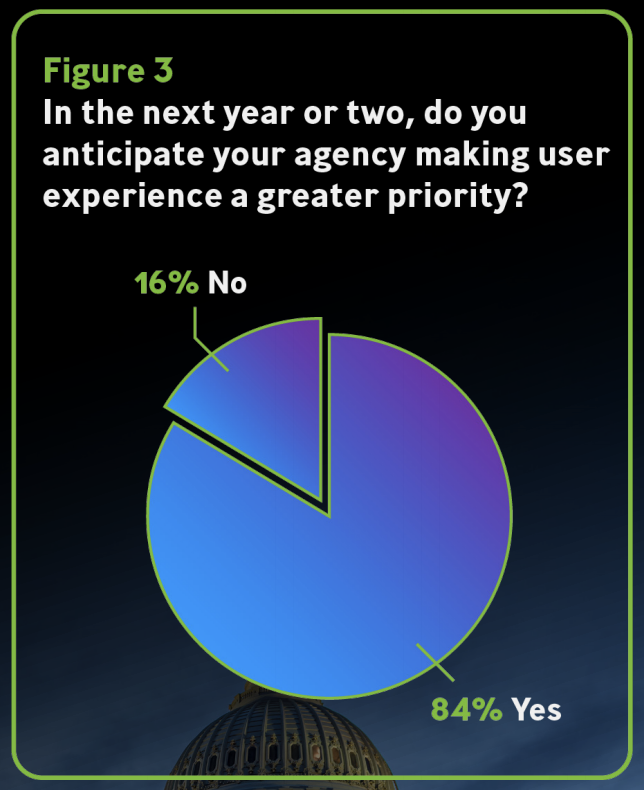

Indeed, the shift has been dramatic. When asked if they expect their agencies to prioritize UX in the next year or two, 84% of respondents said yes (see Figure 3).

Several trends have elevated UX as a priority: executive orders and other government regulations, lessons learned from high-profile IT failures, lofty UX standards set by private-sector companies, and the inherent complexity of deploying and managing modernized IT infrastructure.

The Office of Management and Budget, in OMB Circular A-11 Section 280, set out clear guidelines that define federal government customer experience (CX). The guidelines provide expectations for the role of CX, what it should accomplish, and how to measure it.

Noting that 67% of trust in government can be explained by customer experience, OMB concluded that “improving the public’s trust in government happens interaction by interaction,” and that “customer experience has also been demonstrated to improve outcomes such as saving costs, reducing risk, and more effectively achieving stated missions.”

Private-sector companies such as Google and Amazon are strongly influencing the expectations end users have for government interactions. Those companies use artificial intelligence (AI), algorithms, and biofeedback to understand and improve exchanges with users.

“Private sector companies do a lot of analysis to optimize user experience,” Hicks said. “Government agencies historically haven’t had the competitive pressure to put much effort into UX. But the private sector has set customer expectations at a high bar, so now agencies have to provide a better experience.”

Further motivating agencies to improve UX is a desire to not get caught on the wrong end of an embarrassing UX debacle.

When HealthCare.gov launched in 2013 — on the first day of a government shutdown — technical problems abounded. Built to enroll millions of people in health care plans following the Affordable Care Act, the site successfully signed up only a small percentage of would-be applicants in its first week of operation. The episode has become a cautionary tale of poor UX and how not to roll out a new government program.

“It was a watershed moment that demonstrated how complex applications require hundreds of interfaces into backend applications,” Hicks said. “If they are not built, tested and presented properly to constituents, they are bound to fail. That really drove user experience into the forefront of people’s minds. It’s become kind of a bellwether.”

This article is an excerpt from GovLoop’s recent report, “Automatic and Intelligent Observability: Fast Track to Better User Experience.” Download the full guide here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.